The Revolt of the White Lower Middle Class

By Pete Hamill

From the April 14, 1969 issue of New York Magazine.

They call my people the White Lower Middle Class these days. It is an ugly, ice-cold phrase, the result, I suppose, of the missionary zeal of those sociologists who still think you can place human beings on charts. It most certainly does not sound like a description of people on the edge of open, sustained and possibly violent revolt. And yet, that is the case. All over New York City tonight, in places like Inwood, South Brooklyn, Corona, East Flatbush and Bay Ridge, men are standing around saloons talking darkly about their grievances, and even more darkly about possible remedies. Their grievances are real and deep; their remedies could blow this city apart.

The White Lower Middle Class? Say that magic phrase at a cocktail party on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and monstrous images arise from the American demonology. Here comes the murderous rabble: fat, well-fed, bigoted, ignorant, an army of beer-soaked Irishmen, violence-loving Italians, hate-filled Poles. Lithuanians and Hungarians (they are never referred to as Americans). They are the people who assault peace marchers, who start groups like the Society for the Prevention of Negroes Getting Everything (S.P.O.N.G.E.), the people who hate John Lindsay and vote for George Wallace, presumably because they believe that Wallace will eventually march every black man in America to the gas chambers, sending Lindsay and the rest of the Liberal Establishment along with them. Sometimes these brutes are referred to as “the ethnics” or “the blue-collar types.” But the bureaucratic, sociological phrase is White Lower Middle Class. Nobody calls it the Working Class anymore.

But basically, the people I’m speaking about are the working class. That is, they stand somewhere in the economy between the poor—most of whom are the aged, the sick and those unemployable women and children who live on welfare—and the semi-professionals and professionals who earn their way with talents or skills acquired through education. The working class earns its living with its hands or its backs; its members do not exist on welfare payments; they do not live in abject, swinish poverty, nor in safe, remote suburban comfort. They earn between $5,000 and $10,000 a year. And they can no longer make it in New York.

“I’m going out of my mind,” an ironworker friend named Eddie Cush told me a few weeks ago. “I average about $8,500 a year, pretty good money. I work my ass off. But I can’t make it. I come home at the end of the week, I start paying the bills, I give my wife some money for food. And there’s nothing left. Maybe, if I work overtime, I get $15 or $20 to spend on myself. But most of the time, there’s nothin’. They take $65 a week out of my pay. I have to come up with $90 a month rent. But every time I turn around, one of the kids needs shoes or a dress or something for school. And then I pick up a paper and read about a million people on welfare in New York or spades rioting in some college or some fat welfare bitch demanding—you know, not askin’, demanding—a credit card at Korvette’s … I work for a living and / can’t get a credit card at Korvette’s … You know, you see that, and you want to go out and strangle someone.”

Cush was not drunk, and he was not talking loudly, or viciously, or with any bombast; but the tone was similar to the tone you can hear in conversations in bars like Farrell’s all over this town; the tone was quiet bitterness.

“Look around,” another guy told me, in a place called Mister Kelly’s on Eighth Avenue and 13th Street in Brooklyn. “Look in the papers. Look on TV. What the hell does Lindsay care about me? He don’t care whether my kid has shoes, whether my boy gets a new suit at Easter, whether I got any money in the bank. None of them politicians gives a good goddam. All they worry about is the niggers. And everything is for the niggers. The niggers get the schools. The niggers go to summer camp. The niggers get the new playgrounds. The niggers get nursery schools. And they get it all without workin’. I’m an ironworker, a connector; when I go to work in the mornin’, I don’t even know if I’m gonna make it back. My wife is scared to death, every mornin’, all day. Up on the iron, if the wind blows hard or the steel gets icy or I make a wrong step, bango, forget it, I’m dead. Who feeds my wife and kid if I’m dead? Lindsay? The poverty program? You know the answer: nobody. But the niggers, they don’t worry about it. They take the welfare and sit out on the stoop drinkin’ cheap wine and throwin’ the bottles on the street. They never gotta walk outta the house. They take the money outta my paycheck and they just turn it over to some lazy son of a bitch who won’t work. I gotta carry him on my back. You know what I am? I’m a sucker. I really am. You shouldn’t have to put up with this. And I’ll tell ya somethin’. There’s a lotta people who just ain’t gonna put up with it much longer.”

It is very difficult to explain to these people that more than 600,000 of those on welfare are women and children; that one reason the black family is in trouble is because outfits like the Iron Workers Union have practically excluded blacks through most of their history; that a hell of a lot more of their tax dollars go to Vietnam or the planning for future wars than to Harlem or Bed-Stuy; that the effort of the past four or five years was an effort forced by bloody events, and that they are paying taxes to relieve some forms of poverty because of more than 100 years of neglect on top of 300 years of slavery. The working-class white man has no more patience for explanations.

“If I hear that 400-years-of-slavery bit one more time,” a man said to me in Farrell’s one night, “I’ll go outta my mind!”

One night in Farrell’s, I showed the following passage by Eldridge Cleaver to some people. It is from the recently-published collection of Cleaver’s journalism: “The very least of your responsibility now is to compensate me, however inadequately, for centuries of degradation and disenfranchisement by granting peacefully—before I take them forcefully—the same rights and opportunities for a decent life that you’ve taken for granted as an American birth-right. This isn’t a request but a demand…”

The response was peculiarly mixed. Some people said that the black man had already been given too much, and if he still couldn’t make it, to hell with him. Some said they agreed with Cleaver, that the black man “got the shaft” for a long time, and whether we like it or not, we have to do something. But most of them reacted ferociously.

“Compensate him?” one man said. “Compensate him? Look, the English ruled Ireland for 700 years, that’s hundreds of years longer than Negroes have been slaves. Why don’t the British government compensate me? In Boston, they had signs like ‘No Irish Need Apply’ on the jobs, so why don’t the American government compensate me?”

In any conversation with working-class whites, you are struck by how the information explosion has hit them. Television has made an enormous impact on them, and because of the nature of that medium—its preference for the politics of theatre, its seeming inability to ever explain what is happening behind the photographed image—much of their understanding of what happens is superficial. Most of them have only a passing acquaintance with blacks, and very few have any black friends. So they see blacks in terms of militants with Afros and shades, or crushed people on welfare. Television never bothers reporting about the black man who gets up in the morning, eats a fast breakfast, says goodbye to his wife and children, and rushes out to work. That is not news. So the people who live in working-class white ghettos seldom meet blacks who are not threatening to burn down America or asking for help or receiving welfare or committing crime. And in the past five or six years, with urban rioting on everyone’s minds, they have provided themselves (or been provided with) a confused, threatening stereotype of blacks that has made it almost impossible to suggest any sort of black-white working-class coalition.

“Why the hell should I work with spades,” he says, “when they are threatening to burn down my house?”

The Puerto Ricans, by the way, seem well on the way to assimilation with the larger community. It has been a long time since anyone has written about “the Puerto Rican problem” (though Puerto Rican poverty remains worse than black poverty), and in white working-class areas you don’t hear many people muttering about “spics” anymore.

“At least the Puerto Ricans are working,” a carpenter named Jimmy Dolan told me one night, in a place called the Green Oak in Bay Ridge. “They open a grocery store, they work from six in the mornin’ till midnight. The P.R.’s are willin’ to work for their money. The colored guys just don’t wanna work. They want the big Buicks and the fancy suits, but they jus’ don’t wanna do the work they have ta do ta pay for them.”

The working-class white man sees injustice and politicking everywhere in this town now, with himself in the role of victim. He does not like John Lindsay, because he feels Lindsay is only concerned about the needs of blacks; he sees Lindsay walking the streets of the ghettos or opening a privately-financed housing project in East Harlem or delivering lectures about tolerance and brotherhood, and he wonders what it all means to him. Usually, the working-class white man is a veteran; he remembers coming back from the Korean War to discover that the GI Bill only gave him $110 a month out of which he had to pay his own tuition; so he did not go to college because he could not afford it. Then he reads about protesting blacks in the SEEK program at Queens College, learns that they are being paid up to $200 a month to go to school, with tuition free, and he starts going a little wild.

The working-class white man spends much of his time complaining almost desperately about the way he has become a victim. Taxes and the rising cost of living keep him broke, and he sees nothing in return for the taxes he pays. The Department of Sanitation comes to his street at three in the morning, and a day late, and slams garbage cans around like an invading regiment. His streets were the last to be cleaned in the big snowstorm, and they are now sliced up with trenches that could only be called potholes by the myopic. His neighborhood is a dumping ground for abandoned automobiles, which rust and rot for as long as six weeks before someone from the city finally takes them away. He works very hard, frequently on a dangerous job, and then discovers that he still can’t pay his way; his wife takes a Thursday night job in a department store and he gets a weekend job, pumping gas or pushing a hack. For him, life in New York is not much of a life.

“The average working stiff is not asking for very much,” says Congressman Hugh Carey, the Brooklyn Democrat whose district includes large numbers of working-class whites. “He wants a decent apartment, he wants a few beers on the weekend, he wants his kids to have decent clothes, he wants to go to a ballgame once in a while, and he would like to put a little money away so that his kids can have the education that he never could afford. That’s not asking a hell of a lot. But he’s not getting that. He thinks society has failed him and, in a way, if he is white, he is often more alienated than the black man. At least the black man has his own organizations, and can submerge himself in the struggle for justice and equality, or elevate himself, whatever the case might be. The black man has hope, because no matter what some of the militants say, his life is slowly getting better in a number of ways. The white man who makes $7,000 a year, who is 40, knows that he is never going to earn much more than that for the rest of his life, and he sees things getting worse, more hopeless. John Lindsay has made a number of bad moves as mayor of this town, but the alienation of the white lower middle class might have been the worst.”

“The black man has hope; his life is slowly getting better. The white man of 40 who makes $7,000 sees things getting worse.”

Carey is probably right. The middle class, that cadre of professionals, semi-professionals and businessmen who are the backbone of any living city, are the children of the white working class. If they are brought up believing that the city government does not care whether they live or die (or how they live or die), they will not stay here very long as adults. They will go to college, graduate, marry, get jobs and depart. Right now, thousands of them are leaving New York, because New York doesn’t work for them. The public schools, when they are open, are desperate; the private schools cost too much (and if they can afford private school, they realize that their taxes are paying for the public schools whose poor quality prevent them from using them). The streets are filthy, the air is polluted, the parks are dangerous, prices are too high. They end up in California, or Rahway, or Islip.

Patriotism is very important to the working-class white man. Most of the time he is the son of an immigrant, and most immigrants sincerely believe that the Pledge of Allegiance, the Star-Spangled Banner, the American Flag are symbols of what it means to be Americans. They might not have become rich in America, but most of the time they were much better off than they were in the old country. On “I Am an American” Day they march in parades with a kind of religious fervor that can look absurd to the outsider (imagine marching through Copenhagen on “I Am a Dane” Day), but that can also be oddly touching. Walk through any working-class white neighborhood and you will see dozens of veterans’ clubs, named after neighborhood men who were killed in World War Two or Korea. There are not really orgies of jingoism going on inside; most of the time the veterans’ clubs serve as places in which to drink on Sunday morning before the bars open at 1 p.m., or as places in which to hold baptisms and wedding receptions. But they are places where an odd sort of know-nothingism is fostered. The war in Vietnam was almost never questioned until last year. It was an American war, with Americans dying in action, and it could not be questioned.

The reasons for this simplistic view of the world are complicated. But one reason is that the working-class white man fights in every American war. Because of poor educations, large numbers of blacks are rejected by the draft because they can’t pass the mental examinations; the high numbers of black casualties are due to the disproportionate number of black career NCOS and the large number of blacks who go into airborne units because of higher pay. The working-class white man (and his brothers, sons and cousins) only get deferments if they are crippled; their educations, usually in parochial schools, are good enough to pass Army requirements, but not good enough to get them into the city college system (which, being free, is the only kind of college they could afford). It is the children of the rich and the middle class who get all those college deferments.

While he is in the service, the working-class white hates it; he bitches about the food, the brass, the living conditions; he tries to come back to New York at every opportunity, even if it means two 14-hour car rides on a weekend. But after he is out, and especially if he has seen combat, a romantic glaze covers the experience. He is a veteran, he is a man, he can drink with the men at the corner saloon. And as he goes into his 30s and 40s, he resents those who don’t serve, or bitch about the service the way he used to bitch. He becomes quarrelsome. When he gets drunk, he tells you about Saipan. And he sees any form of antiwar protest as a denial of his own young manhood, and a form of spitting on the graves of the people he served with who died in his war.

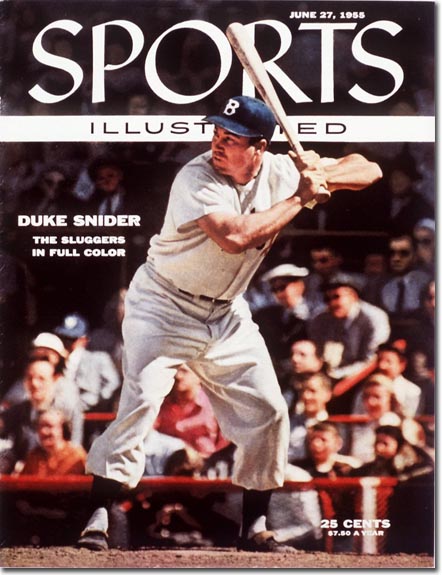

The past lives on. When I visit my old neighborhood, we still talk about things we did when we were 18, fights we had, and who was “good with his hands” in the main events at the Caton Inn, and how great it was eating sandwiches from Mary’s down near Oceantide in Coney Island. Or we talk about the Zale-Graziano fights, or what a great team the Dodgers were when Duke Snider played center field and Roy Campanella was the catcher, and what a shame it was that Rex Barney never learned how to control the fast ball. Nostalgia was always a curse: I remember one night when I was 17, drinking beer from cardboard containers on a bench at the side of Prospect Park, and one of my friends said that it was a shame we were getting old, that there would never be another summer like the one we had the year before, when we were 16. It was absurd, of course, and yet it was true; the summer we were 17, guys we knew were already dying on the frozen ridges of Korea.

A large reason for the growing alienation of the white working class is their belief that they are not respected. It is an important thing for the son of an immigrant to be respected. When he is young, physical prowess is usually the most important thing; the guy who can fight or hit a ball or run with a football has more initial respect than the guy who gets good marks in school. But later, the man wants to be respected as a good provider, a reasonably good husband, a good drinker, a good credit risk (the worse thing you can do in a working-class saloon is borrow $20 and forget about it, or stiff the guy you borrowed it from).

It is no accident that the two New York City politicians who most represent the discontent of the white working class are Brooklyn Assemblyman Vito Battista and Councilman Matty Troy of Queens. Both are usually covered in the press as if they were refugees from a freak show (I’ve been guilty of this sneering, patronizing attitude towards Battista and Troy myself at times). Battista claims to be the spokesman for the small home owner and many small home owners believe in him; but a lot of the people who are listening to him now see him as the spokesman for the small home owner they would like to be. “I like that Battista,” a guy told me a couple of weeks ago. “He talks our language. That Lindsay sounds like a college professor.” Troy speaks for the man who can’t get his streets cleaned, who has to take a train and a bus to get to his home, who is being taxed into suburban exile; he is also very big on patriotism, but he shocked his old auditors at the Democratic convention in Chicago last year when he supported the minority peace plank on Vietnam.

There is one further problem involved here. That is the failure of the literary/intellectual world to fully recognize the existence of the white working class, except to abhor them. With the exception of James T. Farrell, no major American novelist has dealt with the working-class white man, except in war novels. Our novelists write about bullfighters, migrant workers, screenwriters, psychiatrists, failing novelists, homosexuals, advertising men, gangsters, actors, politicians, drifters, hippies, spies and millionaires; I have yet to see a work of the imagination deal with the life of a wirelather, a carpenter, a subway conductor, an ironworker or a derrick operator. There hasn’t even been much inquiry by the sociologists; Beyond the Melting Pot, by Nathan Glazer and Pat Moynihan, is the most useful book, but we have yet to see an Oscar Lewis-style book called, say, The Children of Flaherty. I suppose there are reasons for this neglect, caused by a century of intellectual sneering at bourgeois values, etc. But the result has been the inability of many intellectuals to imagine themselves in the plight of the American white working man. They don’t understand his virtues (loyalty, endurance, courage, among others) and see him only through his faults (narrowness, bigotry, the worship of machismo, among others). The result is the stereotype. Black writers have finally begun to reveal what it means to be black in this country; I suppose it will take a working-class novelist to do the same for his people. It is certainly a rich, complex and unworked mine.

But for the moment, it is imperative for New York politicians to begin to deal with the growing alienation and paranoia of the working-class white man. I really don’t think they can wait much longer, because the present situation is working its way to the point of no return. The working-class white man feels trapped and, even worse, in a society that purports to be democratic, ignored. The tax burden is crushing him, and the quality of his life does not seem to justify his exertions. He cannot leave New York City because he can’t afford it, and he is beginning to look for someone to blame. That someone is almost certainly going to be the black man.

“The revolt involves guns. In places like East Flatbush and Corona, people are forming gun clubs and self-defense leagues.”

This does not have to be the situation, of course. If the government were more responsive to the working-class white man, if the distribution of benefits were spread more widely, if the government’s presence were felt more strongly in ways that benefit white communities, there would be a chance to turn this situation around. The working-class white man does not care if a black man gets a job in his union, as long as it does not mean the loss of his own job, or the small privileges and sense of self-respect that go with it. I mean it; I know these people, and know that they largely would not care what happens in the city, if what happens at least has the virtue of fairness. For now, they see a terrible unfairness in their lives, and an increasing lack of personal control over what happens to them. And the result is growing talk of revolt.

The revolt involves the use of guns. In East Flatbush, and Corona, and all those other places where the white working class lives, people are forming gun clubs and self-defense leagues and talking about what they will do if real race rioting breaks out. It is a tragic situation, because the poor blacks and the working-class whites should be natural allies. Instead, the black man has become the symbol of all the working-class white man’s resentments.

“I never had a gun in my life before,” a 34-year-old Queens bartender named James Giuliano told me a couple of weeks ago. “But I got me a shotgun, license and all. I hate to have the thing in the house, because of the kids. But the way things are goin’. I might have to use it on someone. I really might. It’s comin’ to that. Believe me, it’s comin’ to that.”

The working-class white man is actually in revolt against taxes, joyless work, the double standards and short memories of professional politicians, hypocrisy and what he considers the debasement of the American dream. But George Wallace received 10 million votes last year, not all of them from rednecked racists. That should have been a warning, strong and clear.

If the stereotyped black man is becoming the working-class white man’s enemy, the eventual enemy might be the democratic process itself. Any politician who leaves that white man out of the political equation, does so at very large risk. The next round of race riots might not be between people and property, but between people and people. And that could be the end of us.

Hamill on Hamill

As much as anyone, I’m a son of the white working class. My parents were Catholics who immigrated from Protestant Belfast, in the North of Ireland, because they believed America was a place where a human being would be judged on his merits, not his religion. My father, a member of Sinn Fein, left in the wake of the bloody anti-Catholic rioting in the early ‘20s; my mother arrived the day the stock market crashed in 1929; it’s been all uphill since. My father lost his leg playing semi-prosoccer in Brooklyn in 1931, and spent most of the Depression and the first seven years of his marriage as a $19-a-week clerk in a grocery chain.

During World War Two he worked in a Bush Terminal war plant, and was an electrical wirer in a factory from 1946 until his retirement four years ago. There were seven children, of which I an the oldest, and my father never earned more than $85 a week in his life. The family never took welfare, although they were certainly entitled to it. Instead, my mother worked, first as a nurse’s aide, emptying bedpans and other things in Brooklyn’s Methodist Hospital, later as a cashier at the RKO Prospect.

I quit high school after two years at the age of 16, to work as a sheetmetal worker in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Later, I joined the Navy, studied painting and design and became a writer; that’s another story. My parents now live in Bay Ridge; two of my brothers live in California; one is in the Army, and just returned from Vietnam where he won a Bronze Star; one is a professional photographer; the other is a high school senior, and my sister is a budding journalist. In retirement, my father watches ballgames, reads fiction from Raymond Chandler to Dostoievski, and every once in a while gets a load on for old times’ sake.

My mother still works. It is a tough habit to break.