He was an Original Gangster Of Running. I was a couple inches taller, a few years older. ten pounds heavier and a minute per mile slower, maybe two. Tom had bigger legs. I was a fan. We were in a couple races together, albeit really socially distant. Figure I’m six miles back at Boston.

But enough about me. I have appropriated the intellectual and heartfelt property of Bobby Hodge, Gary Cohen, Jeff Benjamin, Roger Robinson and Toni Reavis et al. to produce this honorific collage. Estimable reporters all, thank you.

I did not know Tom Fleming, but I miss him.

“Somewhere in the world, someone is training when you’re not. When you race him, he’ll win. ” – Tom Fleming

Bob Hodge told LetsRun about the man in 2004.

Hyper-consistent Tom Fleming is proof that good road racers come in all shapes and sizes. Led the 1979 Boston race through 15 miles, setting a torrid pace, yet still hung on for a near-PR 2:12:56.

TOM FLEMING: Bloomfield, New Jersey. 6’0″, 154. Born July 23, 1951 at Long Branch, New Jersey. Running store owner working 40 hours per week. Married. Tom started competing and road racing at age 17. He plans to continue competitive road racing for many years to come. His favorite distance is 30k and he doesn’t have a coach.

BEST MARKS: 1500m, 3:51.6, 2-mile, 8:41.6; 3 mile, 13:41.4; Road: 15k, 45:48; 20k, 1:00:55; 25k, 1:17:22; 30k, 1:30:58; marathon, 2:12:05(75).

TRAINING: Tom’s longest training run was 35 miles; he prefers to race every two weeks. He has been doing the following routine for six years.

Mon–AM, 10 miles at 7:00 pace. PM, 10 miles @ 6:00 pace.

Tues– AM, 10 miles @ 7:00 pace. PM, 14 miles @ 6:00 pace.

Wed– AM, 10 miles @ 7:00 pace. PM, 10 miles hard fartlek.

Thurs– AM, 10 miles @ 7:00 pace. PM, 10 miles @ 7:00 pace.

Fri– AM, 10 miles @ 7:00 pace. PM, 14 miles @ 6:00 pace.

Sat– AM, 10 miles @ 7:00 pace. PM, 10 miles @ 7:00 pace.

Sun– long run 21-23 miles or race.

Tom’s training is… “always the same; some people can’t believe how boring the whole routine is, but I have had success so I will keep it the same.

“Right now,” he continued, talking about back in the day, “my main motivation for running is: 1. I want to be the best marathon runner I possibly can be and 2. I like all the great trips I get around the world for nothing–all I have to do is run, and I really love to run.”

And Tom himself some years later told Gary Cohen a whole bunch of good stuff. On the phone for over two hours and he was not a slow talker.

“I was a newspaper boy in New Jersey and in 1964 out of 104 local newspapers I was named the ‘newspaper boy of the year.’ I was delivering over 1,000 papers per week and making about $105 which was a lot of money back then. As a reward for being ‘newspaper boy of the year,’ Governor Hughes of New Jersey picked me up in Bloomfield with his helicopter; we flew to the World’s Fair in New York City and I got a free pass to go on all of the rides.”

http://www.garycohenrunning.com/Interviews/Fleming.aspx

| GCR: Often an athlete has ‘defining moments’ such as winning an Olympic medal or Super Bowl title that affects his life and forever shapes how others view and relate to him. After more than 35 years since you won the 1973 and 1975 New York City Marathon and were runner up in the 1973 and 1974 Boston Marathon, which of those days was a ‘defining moment’ for you? TF: As I get older it becomes easier to realize the big picture and how those days made a difference in my life. The day that really changed my life was in 1973 when I placed second at the Boston Marathon while I was a senior at William Patterson State College. I don’t think anyone thought I would place that high, but I was training harder than anyone imagined. |

| GCR: How your confidence and what was was your training like leading up to the 1973 Boston Marathon? TF: I was running 140 miles per week which didn’t put me in position to win NCAA titles. I was a four-time All-American, but didn’t win a championship race. The Boston Marathon was the ‘Granddaddy of all Marathons’ and drew me to it. I wanted to race marathons as I was better as the distance got longer. Going into that race I had a Saturday dual meet and ran a 4:16 mile and 13:50 3-mile double on a cinder track. The day before the marathon I told my dad, ‘Tomorrow I’m going to win the Boston Marathon.’ My dad looked at me like I was out of my mind! But I had been training all winter with Olavi Suomalainen who had won in 1972 after I met him in Puerto Rico when I ran the San Blas race. That day had a huge impact on me because I e from that day onward that I would win it one day, though I ended up being wrong. |

| GCR:When you won your first New York City Marathon in 1973 what was your race strategy, how did the race develop and what was the feeling to win what was growing into a respected large big-city marathon? TF: I decided to run the New York City Marathon that year because I only lived 12 miles away. I figured that I should win as I usually won all of the races in Central Park and had a period of about two and a half years where I never lost a race at any distance in the park. It was right ‘in my back yard’ and I raced in Central Park almost every weekend. Coming in second place in Boston made me believe that I could be good. It validated that if I worked hard that good things would happen so I kept working hard. My mom and sister rented bikes and rode along while I was running the 1973 New York City Marathon. They were glad I was running so they could get some exercise. There were skate boarders, bikes and all sorts of people using the park. As I was coming toward the finish a policeman pulled alongside my mother and said, ‘Please lady, move away.’ My mom responded, ‘Hey, that’s my son!’ It was a fun time and gave me a great foundation to grow as a runner. I made a comment once that was taken out-of-context when I said years later, ‘If I knew the New York City Marathon was going to be such a big thing I would have won it five times’ as I didn’t race it every year. I like the New York City Marathon but the Boston Marathon is my love even to this day. I would give up my two New York Gold medals for one Boston Gold. |

| GCR: In the 1970s there were often prizes such as bikes or small kitchen appliances awarded to runners since prize money wasn’t allowed. Didn’t you win an around the world plane ticket from Olympic Airways as 1973 NYC Marathon Champion? TF: That is true and is an interesting story. In 1973 Olympic Airways was the race sponsor and offered that prize to the winner, though I didn’t know about it until after the race. I did know the winner got a big three foot tall trophy which has since been broken though I did keep the label that says ‘New York City Marathon Champion.’ At the awards ceremony they put a laurel wreath on my head and Mayor John Lindsay gave me my trophy. Then this woman gave me what looked like a check, but it was an Olympic Airways ticket. The woman happened to be Nancy Tuckerman, who had been President Kennedy’s secretary at the White House. The connection was that Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ husband, Aristotle Onassis, owned Olympic Airways. My ticket said I could go around the world either from east to west or from west to east and that I could stop anywhere I wished. That’s how I got to Europe and competed in European track meets. I travelled with Marty Liquori and Dick Buerkle and had my first European running and racing tour. I was no track star but held my own as I travelled around the world. |

| GCR:In 1975 when you won your second NYC Marathon title were you the pre-race favorite, did anyone stay with your pace or did you run solo most of the way? TF: It was a very hot that year on race day – around 75 or 80 degrees and I was out in front early. So I ran it like a hard tempo run. My time that year of 2:19:27 was very respectable for a solo effort and six minute margin of victory on the Central Park rolling hills on a hot day. |

| GCR: How different was the 1976 edition of the NYC Marathon when it left the four-lap setup in Central Park to race in all five boroughs, what was your race plan and how did that race develop? TF: I liked the new race course and thought it was great that more spectators could see our sport as we had a cool sport that many hadn’t been exposed to. We ran along the East River and the course was very hard that year so Bill Rodgers’ 2:10:09 was a phenomenal time. I was with the lead pack until about 14 miles. Then Bill put in a strong move on a bridge and left everyone. The race was over by 16 miles and the leaders were now in one long line. I ran as well as I could and placed sixth in 2:16:52. Even today in New York the leaders use Bill’s strategy and, if he was at his racing best now, he’d go right with them. |

| GCR: In 1970 when you were a college sophomore at William Paterson University you finished second in the first NYC Marathon on a hot 80-degree day. How did you decide to run in the race and were you with the leaders most of the race? TF: My first marathon was at Boston that spring and I finished around 2:37 in 63rd place. Then I ran a marathon out in Pullman, Washington as I was selected to run at the Olympic Training Center. The New York City Marathon in 1970 was my third marathon and I ran because it was ‘in my backyard.’ I thought I won the race as I didn’t know that Gary Muhrcke was ahead of me. I was a bit upset as I thought I was winning – but there was no finish tape stretched as if I was the winner. |

| GCR: It was and always has been uncommon for college runners to serious race the marathon. How did you end up doing this unusual distance racing? TF: I had started running toward the end of my junior year in high school so I only developed so much as a prep. If I had been very fast and got a college scholarship I never could have done what I did as no coach would have let me run marathons. It was a blessing that I was at a small school without excessive academic or athletic pressure and I was able to do what I wanted to do. |

| GCR: Switching gears up the road to Boston, you were twice the bridesmaid in 1973 and 1974 in the Boston Marathon. Relate how each of those races developed and ‘critical points’ that were the difference between winning and placing second. TF: In 1973 I ran from well behind. My plan at Boston was always to finish fast and I kind of miscalculated that year. Jon Anderson got away from me and I never caught him. In 1974 I definitely screwed up when Neil Cusack made a smart move early. I was very strong at the end, but needed a couple more miles to catch him as I let him get to far out in the lead. The critical point was in not staying closer when he picked up the pace. |

| GCR: You ran your personal best marathon at the Boston Marathon in 1975, finishing third in 2:12:05. What are your recollections of that day which ended up being the first of Bill Rodgers four wins in Boston? TF: Bill was having the race of his life and no one was going to beat him that day. I was in second place late in the race and didn’t offer any resistance when Steve Hoag went by me as I just couldn’t take coming in second three years in a row. |

| GCR: A final question about the Boston Marathon – in 1979 you pushed the pace and had at least a 100 yard lead before the halfway point until Garry Bjorklund caught you about 14 miles. You ended up a strong fourth place in 2:12:56. Was this your time to just ‘go for it’ and see if anyone could beat you? TF: Looking back, I think that was the right strategy for me if I was going to win the Boston Marathon, though maybe the wrong year. In 1973 or 1974 it may have worked, but the field in 1979 was very, very tough. There were some great runners and Rodgers, Seko and Bjorklund ran very fast. |

| GCR: You came close to making the 1976 Olympic team in the marathon when you finished fifth at the Olympic Trials in Eugene. With Frank Shorter and Bill Rodgers as favorites to make the team, what was your strategy before the race to contend for the final spot? Is there anything you could have done differently to possibly challenge third and fourth place finishers, Don Kardong and Tony Sandoval? TF: I didn’t have a particular strategy except knowing it would take a very good day to make the team. It was warm but the pace felt easy. I had an average race, but you can’t have an average race and expect to make the Olympic team. I was in contention for much of the Trials race, but after about 22 miles I faded. You have to be on top of your game if you are fighting with the best runners for an Olympic spot and I wasn’t. Sometimes it is just timing and I missed peaking at the right time. The shame was that two months later when the Olympics were held I was probably in the best shape of my life. |

| GCR: You finished fourth at Fukuoka, Japan in 1977 which was at the time the unofficial World Marathon Championship. How was it racing internationally and racing so well on the world stage? TF: At that time the two biggest non-Olympic marathons were at Boston and Fukuoka. I enjoyed racing in Japan and always raced well there. The Japanese seemed to like me as I was a big runner at six feet one inch and with my long hair and beard I stood out. Fukuoka was a great course and a fun place to run. |

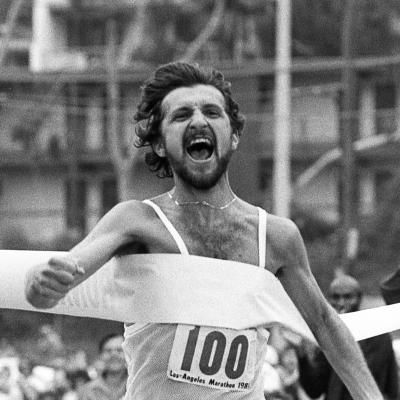

| GCR: You posted victories at the 1978 Cleveland Marathon, 1978 Toronto Marathon and 1981 Los Angeles Marathon. Is there anything that stands out from these marathons regarding your competition, the courses or other memories? TF: In Cleveland I was looking for some redemption as I hadn’t raced well at Boston. Chuck Smead was my top competition though I was able to get away fairly early. The course was beautiful along the lake. One surprising memory was when the lead motorcycle policeman led me off course about a half mile from the finish. When I realized I was off course the feeling that went through me was not good. But I retraced my steps, lost about 30 seconds but still won. The Los Angeles Marathon course was the hardest course I ever ran as it started at the Hollywood Bowl and went through Pacific Palisades. That day I probably could have run 2:11, but I just cruised. Kenny Moore was covering the race for Sports Illustrated and told me it didn’t even look like I was running hard. The race winner got $25,000, but my deal when I agreed to race there was that I would get an extra $25,000 if I was the winner. Believe me – $50,000 was a lot of money in those days. I was in great shape as Bill Rodgers and I had a good winter of training in Phoenix. I wanted our sport to go completely over-the-table with prize money and that is where Bill and I disagreed. I understand his viewpoint as he was getting under-the-table appearance fees. But he also understood my point of view. In Toronto I raced my old rival, Jerome Drayton, who had won at both Boston and Fukuoka, and he took off early. The father of Scotsman Paul Bannen, who ran for Memphis, stepped out with his heavy Scottish brogue with about two miles to go and shouted ‘Tommy, he is right ahead of you and he’s dying!’ I couldn’t see him until about a quarter of a mile to go and caught him with 200 yards left. That taught me to never give up in a marathon as you never know what could happen to those in front of you. My advice to others is to always run through to the finish line. |

| GCR: Did you have any other races where you surprised yourself with your performance? TF: Not as much in the marathon as in two track races in Europe. When my 5,000 meter personal best was 14:11, I came through a 10,000 meter track race in Europe in 14:10 which was a bit frightening. That is an amazing thing about track racing in Europe – when you step on European soil and get in front of those crazy crowds something magical can happen. I only won one track race in Europe which was on a 92 degree day in Finland. I’m convinced that the only reason I won is because I had been training in the summer heat and was the only entrant who was used to such high temperatures. But on a given day anything can happen – you never know. |

| GCR: How special is it to be the three-time winner of the Jersey Shore Marathon since you are a ‘Jersey boy’? TF: I was born in Long Branch, New Jersey so I ran the Jersey Shore Marathon as it was in my father’s old neighborhood. I basically used them as training runs. But those three years it was fun having some of my dad’s old friends out there cheering for me. The last year I received the beautiful Johnny Hayes Memorial Trophy from Johnny Hayes’ daughter. That was very special as Hayes was the Olympic Marathon Champion in 1908. |

| GCR: At one time, you held American records in the 15-mile, 20-mile, 25K and 30K distance events. Do you feel that these intermediate distances may have been your strong suit when compared to the marathon? TF: Probably my best distance was 30 kilometers. I remember one time when Bill Rodgers and I ran a scorching fast 30k on a point-to-point course from Schenectady to New York. Most of my American Records were no longer valid after new standards were implemented regarding point-to-point versus loop courses and elevation changes. It was fun to aim for those records as many of the races were set up for that purpose. My 20k, 15-mile and 25k records were set on the track so I was running many laps around the oval. If you want to see some bloody feet – run 40 or 50 laps around a track in spikes and you’ll find that your feet will be absolutely shredded. We had a plan which was basically to run five minute mile pace and to see how many 75 second laps I could do. You’re going to win lots of races on the road and track if you can run 5:00 pace per mile. It was a tough day as it was hot and I was taking fluids every two laps – I ended up sick afterward. |

| GCR:When road racing was growing in the 1970s didn’t you have a bit of a duel with Jeff Galloway at the Charleston Distance Run 15-miler? And what is the story of your lengthy conversation with Jesse Owens at the pre-race dinner? TF: Jeff Galloway beat me at the first Charleston Distance Run, but the highlight of that race has nothing to do with the events that occurred while we were racing. The night before at the pre-race dinner I was invited to the home of Race Director, Dr. Cohen, and I sat next to Jesse Owens for two and a half hours. Sitting next to a legend for that amount of time was unbelievable as were the stories he told. After he won his fourth Gold Medal at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin the films show Adolph Hitler not shaking his hand. Jesse told me the real story of what happened is that, after he won his fourth Gold Medal, when they were in the bowels of the stadium, Hitler did shake his hand, but he did it where no one could see it. Then Hitler told Jesse, ‘You are the greatest athlete I have ever seen.’ Jesse Owens was a really nice guy and for a runner it was almost like having God sit next to me. |

| GCR: Other top races at intermediate distances in the 1970s included the Wheeling, West Virginia 20k and the Peace Race in Youngstown, Ohio. What are some top memories from those two races? TF: I still go back to Wheeling, West Virginia every Memorial Day weekend and am the Master of Ceremonies for the 20k even though it’s been over 30 years since I first ran the race in 1977. I never won it, but was in the top five finishers several times. I was never in top form because I was usually recovering from the Boston Marathon but it is a race I have a lot of love and affection for. The Peace Race at that time was a long race of 30 kilometers. One year I remember it was the U.S. 30k Championship and John Vitale, Bill Rodgers, Frank Shorter and I were among the ‘stud field’ there to contend for the win. Bill, Frank and I were hammering and just killed each other for about 14 miles and then John Vitale put in a surge, went into the lead and beat us all! There was great road racing at the time and you never knew if you would win or lose as the competition was tough. |

| GCR: Is there one race that tops all others where you duked it out with a top foe and won? TF: The Diet Pepsi Series 10k in New York in Purchase, New York was a good duel between Bill Rodgers and me. Bill had a contract with Pepsi to run all of the races in their series and was kind enough to get me invited due to his connections. The final race was in Purchase where the corporate headquarters was located. Bill and I got into a real tangle in that race where neither one of us could pull away and it came down to a 50 meter sprint at the end. I think the race officials gave me the nod because my nose was bigger – but it was an incredible race and finish. To this day Bill is still mad at me for winning that race! The interesting thing is that this race and others where we competed fiercely weren’t always ‘big deal’ races and there was nothing at stake except our drive to win. So when we felt good we just went for it and often ran sub-29 minute 10k races in the heat of summer. As I mentioned earlier, there were so many good runners that at any race if you didn’t have a good day there was someone there who could beat you. |

| GCR: Stretching the race distance out a bit, in 1982 you set an American Record for 50k at 2:52:30 in winning at Cedar Grove, NJ. How tough was it racing beyond the marathon distance? TF: It was a setup race that Hugh Sweeney did for me around a reservoir where I had run for years. He measured a loop, got it certified and I started doing 2.27 mile loops around the reservoir. We knew that a 2:22 marathon pace would be on the way to breaking the American Record for 50k so that is what I ran. It was actually pretty easy to break the record as I could have run quite a bit faster. I didn’t want to really push myself – I just wanted to aim for the record and see how it went. My fastest mile was the last mile in 5:01 so that told me I could have run faster. I did the race because it was close to home and was a good training run. |

| GCR: Did you think much about training for and racing more ultra marathons? TF: Afterward I had no desire to run any more ultra marathons as I didn’t like them. My personality is that I wanted to be a miler, but I wasn’t fast enough so I stretched it out more and more to the marathon – but that was far enough. I have spoken with Bill Rodgers recently and now that we are old and decrepit we regret that we didn’t do the Western States 100-Miler as we both wish we had earned a finisher’s belt buckle. |

| GCR: In college you placed in the top 30 of the NCAA College Division Cross Country Championships twice with a 29th place 25:32 your junior year in 1971 and a 12th place 25:05 on the Wheaton College Course the following fall. What stands out from these national championship races? TF: The fields were loaded back then with many good runners in the college division and it was hard to place high in the championships. You can imagine how tough the field was when I didn’t even place in the top ten in 1972 and I finished second in the Boston Marathon five months later. |

| GCR: You are the only cross country runner in New Jersey Athletic Conference history to be a 4-time Cross Country individual champion. Were there any tough competitors in the NJAC or close finishes? Did you have any secret to your success on that course? TF: The first two years there was more competition than in my senior and junior years. The meet was held on a tough course in an area about ten miles from my house and there was a big, long hill toward the end. It suited me well and if you were aggressive early you could really hurt your competitors. I was nervous my senior year when I was going for my fourth title since no one had ever done that. I remember talking to a friend who was there as a spectator and saying, ‘Meet me at the mile marker because I’m going out fast.’ I ran a 4:26 first mile and had a lead of 50 or 100 meters as nobody else was going to run that fast. It is a great course that they still use today. I felt good about winning four straight years and am sort of surprised no one else has matched me. But runners are different today – I didn’t think much about whether I was running cross country, on the track or on the roads. I thought of just being a runner and my training didn’t change much. I was always trying to build a bigger base, do tempo running and incorporate more speed. I was fortunate to have a body that never broke. I never missed days due to being sick or injured. |

| GCR: What was the main impact on you of Dean Shotts, your coach at William Paterson State College? TF: Coach Shotts started coaching during my second year and was happy to do some travelling when I qualified for big meets. When I made my first U.S. team and earned my first U.S. uniform he went along with me to San Juan, Puerto Rico where I won that marathon. His best contribution to my time in college is that we had a fun time and a loose group. |

| GCR: When you started in college was the 1968 NJAC Cross Country champ, Tom Greenbowe, from your college still there to run with your freshman year? Did any other teammates help you as you transitioned from high school to college? TF: When I started running as a freshman I was the top runner on the team as I had got my times down to around a 4:16 mile and 9:10 2-mile over the summer. That was from years of soccer and only about 18 months of running. I liked the individual aspect of running where I did the work and I reaped the rewards and credit. Tom was there, was a nice guy and is a doctor now. Another runner, Dave Swan, is unique in my life as Dave took me to my first road race which was a 20k in Binghamton, New York in August of 1969 between high school and college. Somehow I won the race though I was dehydrated and dizzy afterward. The drive home took seven hours as we were in the biggest traffic jam in the world – the traffic jam after the Woodstock Music Festival on the New York Turnpike and it took that long to get from Binghamton back to Bloomfield, New Jersey. Now I regret that I didn’t go to Woodstock – but I was an athlete. You wouldn’t believe how much marijuana smoke was in the air and just by driving along with all of these pot-smoking young people I must have inhaled about 12 joints just from second hand smoke! That was the longest day of my life. |

| GCR:Are there any other races that stand out from your collegiate track seasons for fast times or tough competition? TF: My freshman year I broke 9:00 for the 2-mile for the first time indoors and the runner who was ahead and, in effect was a rabbit for me, was John McDonnell who became such a successful coach at the University of Arkansas. John ran 8:58 and I ran 8:59 on an old wooden track at Lawrenceville Prep that was ten laps to the mile. Another standout memory was the weekend at the NCAA track championships where I placed in the top four in both the 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters. Thursday I ran the 5,000 meter trials, Friday the 10,000 meter final and Saturday the 5,000 meter final. That’s a tough triple racing twelve and a half miles on the track in spikes when just six weeks earlier I had placed second at the Boston Marathon. During introductions all runners receive a good hand and when they announced I had placed second in the Boston Marathon I could tell amidst the cheering that there was an undercurrent of incredulousness in the stands. |

| GCR: Though you consider yourself to be best at long distance racing, did you enjoy the collegiate track and field atmosphere? TF: I liked my school and teammates and I ran all kinds of races in dual meets. I was competitive in the mile, would get crushed in the half mile and usually win the three-mile. We had six or seven dual meets and I was focused on helping our team win as I enjoyed the feeling of belonging to a group. It was a good feeling that my buddies needed me to race well just as I needed the jumpers and hurdlers to do well. I take this same mentality to the runners on the high school team I coach and let them know that whatever their event is it is their job to do it well. Looking back it seems silly that I ran the half mile, but maybe it was smart. Maybe what we’re missing today is that we need some more variety. Maybe high school kids should run the 800 meters, mile, two-mile and longer road races. If the distance kids get crushed in the 800 meters it still can help them with their leg turnover. |

| GCR: In high school you made the move from team sports such as baseball, football, soccer and basketball to distance running. What was the appeal about running, what events did you race and did you show a talent fairly quickly? TF: My high school coach, Paul Williams, was an excellent coach and he is still the president of the county coaches association. Paul knew then what I know now – that it is all about desire and hard work. I liked in track how my personal success depended on what I did – if I worked hard I would reap the rewards, which sometime doesn’t happen in team sports. We had a great track team and won the state championship my senior year. Many of my teammates went to big schools. I was one of the few that went to a smaller college as I don’t think most colleges even knew I was graduating since it was just my second track season. I knew I could run fast and by running more and more I got better quickly. I ran a 4:21 mile and 9:22 2-mile in high school and placed second in the State Group Four 2-mile. What I also like about the sport of running is that you don’t have to go to a big time school to be a big time runner. |

| GCR: How did the events of the late 1960s such as the Vietnam War shape you during your formative teenage years? TF: I was obviously aware of what was going on with the Vietnam War and didn’t want to go there. I knew that if you were a good student and athlete it could help you to keep out of the war so that was my thought process for four or five years. I had a student deferment and focused on being a good student and athlete. I had compassion for the veterans who served but I didn’t want to be one. My focus was to be the best runner that I could be. |

| GCR: What was your training mileage in high school, college and beyond? TF: When I first started out in high school I was running 50 to 60 miles a week. After I graduated from high school I ran from 75 to 86 miles a week that summer. I was already getting good results from that level of mileage as I ran a 2:30 marathon. I knew that I had built up endurance over the years from playing soccer but needed more miles to continue building my distance base. I kept steadily increasing my mileage during college so that by the time I graduated I was up to 130 to 140 miles a week. I think the high mileage and avoiding injuries were the keys to my success. |

| GCR: Did you ever do any extremely high mileage weeks just to ‘test the waters?’ TF: My biggest training weeks ever were two 200-mile weeks that Bill Rodgers and I did together – one week at his place and one week at my place. We either did two 15-mile runs or three 10-mile runs each day. Both times it was disastrous as it was way too much running and whether we did two 15-milers or three 10-milers it didn’t work. All we were doing was eating, sleeping and running and we both agreed it was too much. I found that my best high mileage weeks were around 160 miles. I would run 150 to 160 miles a week for about five weeks when I was getting ready for the Boston Marathon. It felt pretty easy, but 200 miles a week was insane. There just wasn’t enough time to recover and we couldn’t eat enough food to nourish our bodies. |

| GCR: How far did you typically go on your long runs? TF: Most of my longest runs were 22 to 23 miles. If I wanted to get in 30 miles or more in a day, I would run 22 to 23 miles in the morning and another eight or ten miles in the afternoon. |

| GCR: Speaking of running a second workout after a long run, I have heard that you would occasionally run a 20-miler in the morning and then mile repeats in the afternoon to see if you were in really good shape. Is there truth to this? TF: I probably only did this two or three times in my career, but that is what many people seem to remember. Now as a coach I look at a day like that and realize it is a mixing of different training elements of an endurance run and then tempo which we shouldn’t do. My philosophy is to build volume to allow a runner to be faster on the track, but you need to be careful when doing both simultaneously as it can be a dangerous combination that leads to injury. |

| GCR: What type of pacing did you incorporate on your distance runs with conflicting thoughts from some who suggested long slow distance, long fast distance or long variable distance? TF: I ran how I felt on a particular day. If I felt good I might run a 20-miler in an hour and fifty minutes which is 5:30 pace per mile. If I was tired it could take two hours and ten minutes which was a full minute per mile slower. I think that was my secret – I listened to my body. If I felt good I cranked up the pace, but if I didn’t I slowed down while still running the miles. I realized that every run cannot be a high performance run as it just isn’t humanly possible. In some way this thought process helped me as I always got the miles in even if I had to slow down. But when I was winning marathons it was rare for me to run over six minutes per mile. |

| GCR: Through the years, based on whether you were training for cross country, track or marathon racing, what were some of your favorite track workouts and road sessions? What are your thoughts about the concepts of ‘variety’ and ‘peaking’ in training? TF: I always like ten times 1,000 meters at a little faster than marathon pace. I found it was strenuous, but not hard. I liked doing five times a mile in 4:45. When Billy Squires was helping with some suggestions, I liked one where we would pick it up to 5:00 pace for two or three miles in the middle of a longer run. There was one ’10-mile’course we used that was actually 9.7 miles and I ran a 3-mile stretch as fast as 13:50 during a run. Years later Joe Lemay, who I coached, found out what I had done and he took off to break it. His first mile was 4:30 and I thought, ‘Oh, oh – he wants it.’ He ended up running a 13:40 and two weeks later he won the Jacksonville River Run 15k. It’s a different type of training and is hard. I tell high school kids now, ‘Whatever workout you don’t like is probably the one you need.’ I also believe you need to train at a variety of speeds over a variety of distances. The more you do that the better off you are. Runners also need to realize that they don’t have to do some speed, tempo and a long run every week. Sometimes they just need to jog for a couple of weeks and do no tempo runs or pickups. I always tried to peak twice for fall cross country and for the Boston Marathon. I didn’t aim to peak at New York as it was too early in the fall back when it was in September or October. Peaking in the spring for the Boston Marathon was ideal after a strong fall and winter of training. |

| GCR: You are known for saying, ‘Somewhere in the world someone is training when you are not. When you race him, he will win.’ Was this a driving force behind your disciplined training philosophy? TF: You have that quote exactly right as it has been framed and I’m looking at it on the wall right now. The original thought was what I said before my first Boston Marathon. I believed it then and I still believe it today. I don’t care how good you are as someone is always out there. I felt that there was always someone breathing down my neck that wanted to beat me so, God willing, I would be out there training every single day. |

| GCR: This thought process extended to many of us in the 1970s. I remember my senior year in high school running ten repeats of 440 yards on Christmas morning before the day’s festivities and thinking that no one trained harder than me that day. Is this similar to how you thought? TF: Yes, it was and I had you beat as one Christmas I ran 14 miles in the morning and 14 miles in the afternoon for the same reason! You would have made it with my group – you would have been fine! |

| GCR: How important is the mental part of training and racing and developing the ability to endure increasing levels of discomfort? TF: It is huge. I never used a sports psychologist, but I was doing race visualization as I thought I had to be mentally tough to race well. I did wonder if it was the training that made me tough in the head or the toughness in my head that let me do the training. I believe you have to have both. Runners also cannot have a fear of losing as we all lose races. As a young kid I always felt I had to go for it. When I played soccer and there was a corner kick I knew that if I wanted to score a goal I had to get my head on the soccer ball. I took that same mentality to running. I believe that on a given day if everyone has been running 140-mile weeks and other elements of training that anyone can win. So I thought, ‘Why can’t it be me.’ Too many teenagers I coach today think they might lose and I tell them, ‘You might lose, but this is what your planned pace is and let’s give it your best shot because you might win.’ Today we have the availability of sports psychologists, but all people have to do is to believe in themselves. If you have good talent and believe in yourself you will go very far. |

| GCR:What have been the positive effects of the discipline and tenacity learned from running on other aspects of your life? TF: It is a big factor in my success in other areas. Do I think I can do anything? No. But I believe I can give 100% at anything and then I can look in the mirror and know that it is the best that I can do. If someone gives 100% in the business world they will probably be a millionaire. When I had my running store business I liked to hire runners who were training hard as I knew that if someone was running 20 miles a day and coming to work that he was mentally tough. |

| GCR: Did you have a chance in the late 1970s to train much with members of the Greater Boston Track Club or other top distance runners? TF: Bill Rodgers and I trained together a lot with us spending two weeks at my house or two weeks at his house. In the springtime I would spend more time in New England training for Boston. Bill and I also spent some time in the winters training in Phoenix. |

| GCR: With the luxury of hindsight, is there anything you could have done differently in training and racing focus that may have resulted in better performances? TF: I am okay with how I did and will take my record. I ran 27 marathons under 2:20 and I’m happy with that. But did I make mistakes? Absolutely. There were times I over trained. Maybe I could have used a coach especially to get me to take some time off when I may have needed it. When I worked with Billy Squires for two years he gave me a bit more ‘purpose’ to certain days training with tempo running and recovery days, so if I did it over again there are a few things I would change in my training. When I look back at my personal best times on the track, they were all set in Europe when I focused on fast track racing. It may have helped my road racing and marathon performances if I had concentrated periodically more on track racing. My best 10k was only 28:42 and it may have helped my marathon racing if I would have concentrated a bit more on decreasing my times in the intermediate distances. But overall it was a good running career. |

| GCR: Who were some of your favorite competitors and adversaries? TF: My greatest adversary was my friend, Bill Rodgers, who in my opinion was one of history’s greatest marathoners and was born to run. Another adversary whom I really admired was England’s Ron Hill who won the 1970 Boston Marathon. He is a real character and God threw away the mold when he made Ron. He was ahead of his time in the way he thought and was a pioneer in many ways. The reason I wore a mesh shirt is because he wore a mesh shirt. He was the first runner and I was the first American to do so as we tried to find ways to stay cooler while running. He wasn’t as much my competitor as a running God who helped me and was very nice to me on my way up. When I finished a few places ahead of him one year at the Boston marathon he was one of the first runners to congratulate me. Frank Shorter was a great competitor and with two Olympic medals it doesn’t get much better than that. |

| GCR: There is a story about you meeting and being inspired by Horace Ashenfelter, 1952 Olympic 3,000 Meter Gold medalist. How did that transpire? TF: He lived in the next town down the road from me when I was a senior in high school. The way I first heard about his achievement was when I ran against a boy from Glen Ridge High School named Tommy Ashenfelter and some kids said his dad had won an Olympic Gold Medal. So I said, ‘Tommy, does your dad really have a Gold Medal?’ He said, ‘Yes, he was the 1952 Olympic steeplechase champion.’ I told him I’d love to see the Gold Medal so I rode on my bike to his house which was only about two miles away. I rang the door bell and Mrs. Ashenfelter came out and showed me the Gold Medal. Horace wasn’t there as he was working, so I met him later. I am still friends with Tommy and tell him that he never knew the impact that had on me as I’d never seen any Olympic Medal, much less a Gold one. I saw Horace last Thanksgiving at the Ashenfelter 8k Thanksgiving race and still see him a few times each year. |

| GCR: You currently coach at Montclair Kimberley Academy and founded the Running Room, which has since closed, in Bloomfield, New Jersey. What are some of the highlights of your coaching? TF: It has been great coaching as I have the kids I coach run on the same loops I trained on and they can’t believe I always know where they are. It’s a great advantage for me to coach as we have a brand new training facility at Montclair and nice areas to train. When my Running Room teams won the national championships is was awesome as they were all New Jersey or Pennsylvania girls. It was a fun time but retail sales were tough so I closed the store several years ago. I like what I’m doing in life now with teaching fourth grade and coaching high school kids. Now I’m doing what I should be doing which is having an impact on teenage runners as you never know if one of them will have the dream that I had to win the Boston Marathon. I just hope that some kid like me comes along so I can show him tips and shortcuts and then spend a lot of time on the course so we can find a way to win. I would love to do that in the upcoming years. |

| GCR: How satisfying is it to help others succeed compared to your own personal accomplishments? How much more difficult is it to instill in others the necessary discipline, focus and mental toughness? TF: It is better to help others. It gives me an incredible feeling when I can help youngsters to improve. The best coaches aren’t always the ones with championship teams, but the ones who can take a 7:00 miler and turn him into a 5:55 miler. That’s coaching! It is exciting to take kids who aren’t too good at anything and to help them find the one thing they can do better than most kids. This past fall I only had nine boys on my high school team, but all of them broke 18 minutes for 5k. Our goal for next fall is for every one of them to get a minute faster and, if they do, they can be county champions. Once these kids hear my passion, they get that enthusiasm inside of them and just go for it. Running fast was easier for me as I only had to be concerned with myself, but it is more rewarding to get a group of kids succeeding together. |

| GCR: What are the effects of the increased distractions of today’s society and the fact that most American youth are more ‘well off’ than a generation or two ago and may not be as hungry for success or willing to work as hard? TF: It is harder for today’s kids with all of the distractions and the demands and desires to make money, get a good job and to live in a big house. It wasn’t like that with me – I just wanted to go out and run. The most important thing I owned as a teenager was a pair of running shoes and, ironically, I haven’t paid for a pair of running shoes since April, 1973 when I came in second at the Boston Marathon. I still have running shoes sent to me because of a race I ran nearly 40 years ago. My good friend, Freddy Doyle, works for Saucony and sent me a few pairs of running shoes recently. Then he called and wanted to send me some racing flats and asked me our school colors. I told him they were forest green and navy and two days later a pair of racing flats that are forest green and navy arrived at my home! I want kids to want to be good runners not so that they can get free running shoes but so when they are 50 years old they can look back and say, ‘I ran my butt off, I did it because I wanted to and I’m happy with what I achieved.’ Whether they win races or not, running gives a tremendous sense of accomplishment and the success and hard work transfer to other parts of their lives. |

| GCR: The United States was very dominant on the world stage in the men’s’ marathon in the 1970s and 1980s before declining for two decades. Do you see optimism with the resurgence in American marathon running in the past several years? TF: I’m an optimist and, since we’ve got over 310 million people in our country, there has to be another ‘Bill Rodgers’ or ‘Alberto Salazar’ out there. There were so many runners back in the 1970s that just went out, put in the training and ended up running respectable 2:18 or 2:19 marathons – back then they were unknowns though today they’d be studs. I remember back when Bill Rodgers and I were training and Dickie Mahoney, who was a post man, would run 140 miles a week even though he was working full time. Incredibly he ran a 2:14:37 for tenth place at the 1981 Boston Marathon. How good would he have been if he didn’t have to work a full-time job? If enough U.S. runners put in the work, we can have many more marathon runners closer to winning major marathons again. What bothers Bill Rodgers, me and others who have raced very successfully at the Boston Marathon is that none of today’s top U.S. marathoners come to us for advice on how to race well at Boston. We can’t believe it! You would think that my finishing six times in the top ten would make it apparent that I know some tricks that can help. If runners out there who are reading this have a desire to run the Boston or New York Marathons and want to talk to someone who can offer insights into racing smarter and faster, then they should get in touch with me. There are advantages if you know the course. For example, very few of the top runners today even run the tangents and race the shortest course where the race is measured. |

| GCR: What do U.S. marathon runners, as a group, need to do to step up to another level? TF: My personal take on U.S. marathon running is that our top runners are waiting too long. I believe they need to start running marathons when they are twenty years old if they want to have a top-level career. But most runners who are that good are in college on scholarship and no coaches are going to encourage them to race marathons. It is a dilemma we face in this country. Our system in the U.S. doesn’t lend itself to developing great young marathon runners. Another problem is that most runners are overly concerned with what contracts they may sign when they complete college. You know what – just be good like in your dreams and it is there for you. The next American born kid who wins the New York City Marathon or Boston Marathon will be an instant millionaire. But money doesn’t make you run faster. If the reason you are running 140 or 150 miles per week is to be a millionaire you might as well stop now. If you want to be the best runner America has ever seen and to run like Frank Shorter and Bill Rodgers, that has to be your reason for running. As far as marathon race strategy, no American should want to lead a major marathon. Almost every race has rabbits and the fast African runners want to lead, so they should let someone else do the work. I wish I could get my hands on some of our top marathon runners and train them as if their whole life is the Boston Marathon – because if they win their whole life will change. They need to run the course like Bill Rodgers and I did. Greg Meyer, the last American man to win at Boston, practically lived on the course and that’s why he won it in 1983. He was very, very fit and knew the course extremely well. Today the competition is tougher as there are hundreds of Africans racing in the U.S., but Americans can race better and win in Boston and New York. |

| GCR: For twelve years you were the meet director for the Sunset Classic 5-mile road race in your hometown of Bloomfield, NJ which raises money for Special Needs Children in the Bloomfield school system. How rewarding was this and how important is the role running now has in raising funds for so many charities? TF: It is great that our sport has raised so much money for charities. But I do question why our sport of running has become the official sponsor sport of the world. It would be interesting to have a big road race and to have the proceeds actually go into developing top runners in our country. An example would be to raise funds so that all U.S. runners who qualify for the Olympic Trials Marathon would have the opportunity to train with similar runners at Olympic development camps. It is a difficult balance these days between competition and developing great U.S. runners and raising money for charity. But I do believe strongly in the good that running is doing in increasing awareness and trying to find treatments and cures in many areas. Two causes that are dear to me are multiple sclerosis and Special Olympics. So, I do want our sport to help with charitable causes while we also pump money into developing our sport. |

| GCR: You have been recognized for your running achievements by Hall of Fame inductions including the Distance Running Hall of Fame in 2006 and the HOF at William Paterson University in 1980. How special is it to be so honored? TF: It is nice and I am appreciative. There were some inductions that may have happened when I was too young as I didn’t appreciate them as much at the time. I am grateful for the recognition. |

| GCR: How your health and what is is your current fitness regimen? TF: My health is good and I don’t have to take any pills due to health issues. I’m tall at six feet, one inch and my racing weight was around 159 pounds, though now I weigh 210 pounds. I don’t feel like I weigh that much, but that is what the scale says. I play a lot of basketball which was my first love. I play in a 55-59 age basketball league. I walk and jog two or three days a week. I don’t have any desire to go out and run 10-milers. Sometimes at our cross country meets when I’m running from one point to another on the course I’ll hear, ‘Hey coach, you look pretty good.’ I just say, ‘Don’t let looks fool you,’ as I have no desire to run more regularly or to do longer distances. |

| GCR: What goals do you have for yourself in fitness, running and other aspects of your life for the upcoming years? TF: I just hope to continue without knee problems. My last recordings in my running log were back in the early 1990s and I had run around 123,300 miles. I have no joint soreness in my hips, knees or ankles, am thankful for that and hope it stays that way for a long time. |

| GCR: Are there any major lessons you have learned during your life from growing up in New Jersey, the discipline of running and sharing your knowledge and experience with others through teaching and coaching that you would like to share with my readers? TF: What I do well and I believe others should do is to share enthusiasm. Whether in the classroom with nine or ten year olds or at the track with teenagers, I see that by my being genuinely excited about how they are doing, they are apt to try their hardest. If kids do their best, the outcome doesn’t matter as they will deservedly get a big cheer from me. My passion is to convince kids that it’s okay to try hard, they should have no fear of competing or losing, they can win and they can be successful. |

Tom Fleming, 65, New York City Marathon Winner, Dies

By Jeré Longman for The New York Times. April 21, 2017.

Tom Fleming, a two-time winner of the New York City Marathon in the 1970s, when he trained as many as 200 miles a week in a period known as the first running boom, died on Wednesday in Montclair, N.J. He was 65.

His death, apparently of a heart attack, was announced by Montclair Kimberley Academy in New Jersey, where Mr. Fleming was a fourth-grade teacher and the varsity track and field and cross-country coach.

Todd Smith, the academy’s athletic director, said that Mr. Fleming had complained of feeling ill at a meet in Verona, N.J., and was found unconscious near the track in his car, where he had gone to sit. He was pronounced dead at Mountainside Hospital in Montclair.

At the height of a sterling career, Mr. Fleming was the top local runner in the New York area in a number of distances. His contemporaries included Frank Shorter, the 1972 Olympic marathon champion, and Bill Rodgers, a four-time winner of both the New York and Boston marathons.

Mr. Fleming won New York in 1973 and 1975, when all 26.2 miles of the marathon were run in loops of Central Park. (The race expanded to the five boroughs in 1976.) He also won marathons in Los Angeles, Toronto, Washington and Cleveland and had two second-place finishes in the Boston Marathon and a fifth-place finish at the 1976 Olympic trials.

His dedication was summed up in an often-cited quotation: “Somewhere, someone in the world is training when you are not. When you race him, he will win.”

Many of today’s elite marathon runners train about 120 miles a week. Mr. Fleming preferred to run 140 to 150, and for at least two weeks during his career he raised the distance to 200.

“He slept, ran, ate, slept, ran, ate,” George Hirsch, the chairman of New York Road Runners, which organizes the city’s marathon, said on Friday.

While many elite runners train twice a day, “Tom, some days, did three runs, and I know a few days he did four runs,” Mr. Hirsch said. “He was as tough a runner as I’ve known.”

Though Mr. Fleming did not win the race he most coveted — Boston, the oldest annual marathon — it was not for lack of determination. After finishing second or third in Boston one year, Mr. Rodgers said on Friday, “he went back home and went out that night and trained some more.”

In his heyday, Mr. Fleming, a rangy 6 feet 1 inch, raced at 159 pounds. In 2011, he weighed 210, he told an interviewer. Barbara Fleming, his former wife, said in an interview that he had been reluctant to get regular medical checkups, though he had recently lost about 25 pounds.

Thomas J. Fleming was born on July 23, 1951, in Long Branch, N.J. A longtime resident of Bloomfield, N.J., he began his running career as a junior at Bloomfield High School and became an all-American at William Paterson College, now William Paterson University.

In 1973, during his senior year in college, he competed in a track meet on a Saturday, then ran the Boston Marathon two days later, finishing second.

Later that year, he entered the New York City Marathon and finished first. There were only 406 entrants in that race, and Mr. Fleming’s mother and sister rented bikes to follow along as he ran through Central Park.

“They were glad I was running so they could get some exercise,” Mr. Fleming told the writer and coach Gary Cohen.

Near the finish line, Mr. Fleming said, a police officer approached his mother and said, “Please lady, move away,” to which she responded, “Hey, that’s my son!”

His fastest marathon time, 2 hours 12 minutes 5 seconds, came in a third-place finish in Boston in 1975. In 1977, he finished fourth at the Fukuoka Marathon in Japan, then considered the unofficial world championship.

He became an advocate for professional running in an era when Olympians were required to be amateurs and money was paid under the table. Elite marathon runners can now make hundreds of thousands of dollars in prize money and appearance fees.

Affable and charismatic, Mr. Fleming seemed to have as much passion for coaching as he once did for running.

“It is better to help others,” he said in a 2011 interview with Mr. Cohen. “It’s exciting to take kids who aren’t too good at anything and to help them find the one thing they can do better than most kids.”

He is survived by a daughter, Margot, and a son, Connor.

By the early 1990s, Mr. Fleming had recorded more than 123,000 miles in his training log. By the end of the decade, he had effectively stopped running, Barbara Fleming said, because “he was so used to being on top” and could no longer compete at a high level.

“He was intense,” said Mr. Rodgers, his friend of more than 40 years. “He couldn’t jog. He had to race.”

Tom Fleming, Beloved Teacher, Coach, and Marathon Champion, Dies at 65

He twice won the New York City Marathon in the 1970s and shared his knowledge and passion with young runners in New Jersey.

By Roger Robinson for Runner’s World. APR 20, 2017.

Tom Fleming, who won the New York City Marathon in 1973 and 1975, and finished in the top three at the Boston Marathon three times, died on April 19. He was 65.

The cause was an apparent heart attack, according to Montclair Kimberley Academy (MKA) in Montclair, New Jersey, where Fleming taught fourth grade and coached track. He died as he was coaching the middle school track team in a meet in neighboring Verona.

“He was high energy, very empathetic, and had a remarkable ability to reach a wide range of kids, boys and girls,” said Tom Nammack, headmaster of MKA. “He didn’t run an easy classroom but it was a great classroom. Third graders who heard about him kept their fingers crossed that of our three sections of fourth grade, they’d end up in his.”

A prominent and popular figure in the first running boom, Fleming was revered for his dedication, which was exceptional even in that uncompromising generation. The words that hung on his bedroom wall have become legendary: “Somewhere in the world, Someone is training when you’re not. When you race him, he’ll win.”

Born in 1951, Fleming lived in Bloomfield, New Jersey, and he became hooked on running during his last year at Bloomfield High School, 1968–69. He immediately began running 100-mile weeks in training. It was during that era when Frank Shorter, Steve Prefontaine, Jeff Galloway, and many others were committing themselves to the rigors of a sport that had always been dominated by the Europeans and Japanese.

Within five years, Americans were placing at the top. Fleming established himself among them by his passionate will to win, mixed with blunt honesty about the work it takes.

“Tom was a close pal, a great competitor, but down-to-earth,” said runner Mike Fanelli, a lifelong friend. “When I asked recently whether he could have caught Jon Anderson at the 1973 Boston Marathon, he just said, ‘Coulda, shoulda, didn’t.’”

Fleming’s father had been a 235-pound tackle for the Chicago Bears, and though Fleming raced at 145 pounds, he was just over six feet, and he had legs often described as tree trunks. At William Paterson University, he became a four-time All-American, though he insisted that he was equally proud of his double major in special education and elementary education.

At Boston in 1972, he placed 23rd in 2:25. But a year later, still a college senior, he was a contender.

“In contrast to his willingness to run vast mileages alone, he was not a quiet person. He was everything New Jersey—big, boisterous…brash, grinning, a verbal brawler. He considered himself a favorite to win Boston. And why not? He had trained more than anyone else,” wrote Tom Derderian in Boston Marathon.

Fleming was second that year, behind Jon Anderson. He was second again in 1974, behind Ireland’s Neil Cusack, and burst into tears of disappointment at the finish. In the tailwind race of 1975, a new talent named Bill Rodgers thwarted him, blitzing the American record, with Fleming third despite a PR of 2:12:05.

Fleming’s luck was better at the New York City Marathon. He won by almost two minutes in 1973, ahead of his friend Norb Sander, who died last month. Fleming won again in 1975, in 2:19:27, a record for the hilly Central Park course. When the race moved into the city streets in 1976, Fleming was sixth, behind Rodgers and Shorter.

Internationally, Fleming’s most significant performance was fourth place in 2:14:26.2 at the 1977 Fukuoka Marathon, when that race was close to being an annual world championship. His best shot at the Olympics was in 1976, when he finished fifth at the U.S. trials.

He won the Jersey Shore Marathon three times and also had marathon victories at Cleveland, Washington, D.C., Toronto, and Los Angeles. He set American records at 15 miles, 20 miles, 25K, 30K, and 50K.

In 1978, he opened one of the first specialty running stores, the Tom Fleming Running Room in Bloomfield, and he ran it until 1999, when he moved full-time to his other passions, teaching and coaching.

He coached Anne Marie Letko, who became a U.S. Olympian and was third at the New York City Marathon in 1994. And he led the Nike Running Room team to the national women’s cross-country championships in 1990, ’91, and ’92.

Members of the running community were unanimous in their sense of loss and admiration for Fleming.

“In this era of manufactured marathon heroes, I know the real ones. Tom was one,” Rodgers said.

“He just loved to see kids run personal bests, he loved the adrenaline rush of competition, and he loved seeing kids working their hardest to push each other,” said Todd Smith, MKA athletic director. “And it had nothing to do with Montclair Kimberley winning the meet. It was really all about the joy of running and the joy of competition, and the kids, whether they were battling it out to set a course record and win it or battling it out coming down the home stretch in 100th place in a race. Tom loved it all.”

Fleming was inducted into the Road Runners Club of America Hall of Fame and the National Distance Running Hall of Fame.

Remember Tom’s Laugh.

By Jeff Benjamin for RunBlogRun.

On the last Sunday of the month, this writer, along with others, woke up early and continued a ritual which perhaps thousands of runners of all abilities in the New York-New Jersey-New England area had been practicing for close to 5 decades- getting in one’s car early enough to trek over to Bloomfield, New Jersey and arrive by 8 am to go for the Sunday long run with a real-life world-class runner, Tom Fleming.

Later on, runners would make the same Sunday morning trek to Brookdale park in Bloomfield to be advised by that same Tom Fleming, who had then gone on to become a world class Coach, creating successful athletes from High School all the way up to the Olympic level, while teaching 4th grade at Montclair Kimberley Academy in nearby Montclair.

Sadly, this past Sunday’s trek for many was to say goodbye.

Hundreds of Fleming’s’ students, friends, family, former and current students and a host of others paid tribute at a Private memorial service in his honor at the Montclair school. Fleming, who tragically and suddenly died of a sudden heart attack on April 19th while coaching his MKA high school team at a local meet, was remembered by speakers as not only the world class 2:12:05 Boston Marathon nor the two victories in the early Central Park looped NYC Marathons, but as the honest, straightforward and loyal friend, family member, and mentor he became.

Tom Derderian’s masterpiece book “Boston Marathon” aptly describes the larger than life figure who Everyone came to know–

“Tom Fleming from New Jersey was “everything New Jersey” –big, boisterous, the Cassius Clay of New Jersey. In a sport of tight-lipped introverts, Tom Fleming was pure lip-brash, big-shouldered, grinning, a verbal brawler. He would argue any point of view with anyone. He could not keep his opinions to himself.”

Fleming’s MO carried him from a New Jersey state HS champion after only 1 year of training to becoming one of the youngest distance runners to be invited to train and be evaluated at the USA Olympic Training Center in Colorado.

Totally committed and inspired, Flemings’ training consisted of easily breaking 150 miles per week in training and sometimes running 4 times a day, thereby accumulating 200 miles for those particular weeks, and rising to the World Class level. Fleming won fifteen International Marathons and, during that age of the strict, archaic and hypocritical amateur rules, took up with his fellow competitor, the late Steve Prefontaine, desire to fight the hypocrisy of shamatuerism. Posters of runners along with countless books on running and training flooded his room.

Of course as many know Fleming’s great quote wound up on many other runner’s walls as well-“Somewhere in the world, Someone is training when you’re not. When you race him, he’ll win.”

Later on, using that same drive and passion, Fleming went into coaching athletes at all levels as well. His most notable athletes were two who qualified for the Olympic Games – Anne Marie Letko (1996) & Joe LeMay (2000).

Here are some reminisces from Fleming’s friends–

Bob Hodge- One of the Great Boston Area Distance Runners –

“TF Flyer, Tom Fleming, I best remember our time in that vacationing professor’s house in South Miami in the winter of 1980. Tom was pure NJ. Every single morning, TF would run 15 miles and drag me with him through Coconut Grove with the Parrots of April squawking overhead, in the crushing heat and humidity of a Miami winter morning. I woke up to TF’s knocking on the door and then his voice, “Bobby, time for your medicine” By the time we got to the end of the first block, TF was 2-3 steps ahead of me and there he generally stayed. On other days, I only tried to keep him in sight.

TF only stopped on a run to poop and I always hoped he would need to so I could catch a breather. Of course if I stopped for any reason, TF was gone. Though just at the end of our run we would stop at a bridge crossing to look for Manatees that would congregate there. The house had avocado trees which I thought were quite exotic and I tried them for the first time in my life and loved them. We would finish our runs and I would sit on the stoop for an hour staring into space with Pepsi and water, what-not and avocados.

TF would immediately be off to the next thing making plans for the day. We had visits from other runners including Bill Rodgers, Kirk Pfeffer and Guenter Mihelke. We watched the Winter Olympics in the evenings including the USA Hockey Team victory.

In 1980, we were dreaming our own Olympic dreams, that is why we had come to Miami, but now the boycott loomed. One day on our morning run I bonked and just started walking. TF never looked back. My mind was in a storm. “What am I doing here getting run off my feet every freakin day with no Olympics”? When I got back I started packing up my Mustang and getting ready to drive home. TF just shook his head at me. “Carter ain’t gonna stop this thing if the USOC has any balls. if they don’t we just run Boston instead, I would rather win Boston than anything!”

On the weekend TF went to a race somewhere and I traveled to Jacksonville and won the River Run 15K. The hard effort was bearing fruit.

During our time in Florida we traveled to the Ohme 30K in Japan an awesome trip. In 1986 we traveled to New Zealand together, Tom and then wife Barbara and month old child Margo.

So many memories of TF who I last saw this past summer in Eugene at the Trials. See you down the road, buddy.”

Joel Pasternack- Top New Jersey runner and coach and Fleming’s most consistent Training Partner-

“Tom had an affect on so many lives. I Met Tom in the fall of 1969 when my college, Monmouth, ran against Paterson State. After the race, we talked and found out we lived three miles from each other. He said anytime I’m home call and we’ll run. That became a very popular habit of training together for 18 years. Tom has been quoted that I was the person he ran the most miles with, over 10,000. Tom helped me make my big breakthrough in marathon running. In the 1972 Boston I ran 2:34.35 placing 53rd. Then in January of 1973 I ran with Tom for ten miles of the Jersey Shore 26.2. That helped me run 2:25.08 for second behind Tom and his first time under 2:20. We traveled to many races over the years in the 70s with both our dads. The biggest trip was the two of us to the 1972 marathon Olympic trials in Eugene. Like you said Tom always ran ahead and wanted to win. The weather got to him and he dropped out. But after that his career sky rocketed.

In closing Tom was a phenomenal friend to me and my family. He was my mentor and made me the person I am today in life and coaching. I can’t believe I won’t get share all the special things that life brings us with him.”

Greg Meyer-1983 Boston Marathon Champion

“With Tom in the race, you knew it would always be a test of fitness. He worked hard and wanted you to do the same if you expected to beat him. That said, once the race was over, he was the guy entertaining everyone!

One story I’ll never forget is going on a run with him through the woods in NH from the Mt. Washington resort. As we ran down the train we rounded a bend, and there stood two adult moose. City boy Tom looks at me as says “let’s chase them”. I politely said “you go, I’ll watch!” I then told him moose are the most dangerous critters in the states… you don’t mess with them! No fear in that guy!”

Women’s Running Pioneer Kathrine Switzer

“Tom pushed it to the limit in every marathon. He was like a big kid in his enthusiasm. He wanted to slap everyone on the back and make them run with him. He was incredibly supportive of women, as early as 1973, when he encouraged me to run the San Blas Half-Marathon in Puerto Rico, a huge race at that time, despite the disapproving local officials.”

Joe Martino – New England Runner and longtime friend–

“In the fall of 1970, Ed Walkwitz, John Jarek and I were on our way down to run in the Atlantic City Marathon. As we approached New Jersey he suggested that we call Tom and perhaps stay in Bloomfield for the night. Ed had been Tom’s roommate at the Olympic Training camp the previous summer. Apparently Tom told Ed if you are ever in New Jersey that he was welcome to stay. We ended up staying the night at the Fleming’s. I learned from Tom that we were both in the NYC Marathon the month before. Tom was 2nd and I was 13th in 2:56. It was a Very Hot Day on a wicked demanding course. Tom was 19, I was 18 and, Rick Sherlund who became friends with Tom was 16! Rick always tells the story that he crossed the finish line just behind Tom…..But Rick had one more lap to go!

On Saturday morning, we went to Van Cortlandt Park with Tom and his Dad. Tom was running a cross country race, representing Patterson State. He was beaten by a guy from Coast Guard Academy. I think Tom told me it was the only time that he was beaten there.

In 1982 Tom came to Natick, where I was living at the time. He stayed at my place and on Sunday morning he invited me out to Bill Rodgers’s home for a run. Tom showed me lots of running loops which he and Bill trained on- loops right in my back yard. A few days later, I was out on a run and ran into Bill and, long story short, we began training together 4-5 days a week. From then on Tom, Bill and I would get together and enjoy many adventures together.”

Bill Rodgers- 4-time Boston & NYC Marathon Champion

“I met Tom Fleming in February of 74 when we represented the USA in the San Blas Half Marathon in Coamo, Puerto Rico.Fellow American Former Uconn star John Vitale was our third Team member. San Blas is a very tough race- very hilly, hot and humid but, the people were terrific. San Blas was also my 1st International race. We had our USA Uniforms and I was rather excited about reaching this level of competition!

Tom introduced me to European and Boston marathon Champion Ron Hill and other International athletes. Two Olympic medalists from the 72 Munich Games were competing on behalf of Finland, Lasse Viren and Tapio Kantanen. They were considered favorites. I didn’t care and chased them both but the Finns won. I faded badly and John Vitale and I were both passed by Tom who was a prodigious trainer and strong even in the heat. When I was struck by the 78 degree heat at Boston in 73 and dropped out Tom flew to a fine 2nd place.

Over the heady years of the first Running Boom, we became friends and trained together everywhere. We used to travel to Phoenix, Arizona, in February, for the Runners Den 10k and stay with mutual friends Rob and Ann Wallack. Rob and Ann had a beautiful Irish setter who was as wired as Tom and I! The Problem was he was a barker so when he got out of control Rob or Ann would puta collar on him that produced a mild shock to teach him to calm down.

One day Tom thought it would be a good joke to place it over my head as I sat at the breakfast table. I got shocked and jumped into the air! TF was hysterical with laughter as I threw objects at him. He was a supernova of energy but was also funny as heck. He always did great Yoda and Elmo imitations and would be telling stories nonstop as we ran.

In ’77 Tom and I placed 1s and 4th at the Fukuoka Marathon in Japan.

I call Fukuoka the “Japanese Boston Marathon” due to its 70 year history of top marathoners participation.

I believe we still have the highest one, two finish of any American participation at this superb marathon. We celebrated in Tokyo with Plum wine along with our mutual friend, Tommy Leonard, the Boston Bartender who orginated the Falmouth Road Race.

Of course we track, XC and road race athletes toiled under the scourge of Amateurism. But we tried to be Professionals as much as we could..Tom and I were both teachers who ran 125 miles every week, but always wondered why all of us could not be compensated.

I believe Tom Fleming was one of if not the first modern road racer marathoner to go professional with his marathon races in LA and elsewhere in 1980.

The Association of Road Racing Athletes followed Toms efforts in June ’81 with the running of the Cascade Runoff 15k in Portland we were all a bit freer.

Tom went on to Coach XCountry and to teach 4th graders history. The fierce competitor mellowed out under youth influence… he passed the Torch.”

From Alberto Salazar–

“Most of my interactions with Tom took place after we had both retired. He was a few years ahead of me and was probably in his last years of competitive running when I was still concentrating on the track. My earliest memories of him were of someone that was a very tough racer and who trained unbelievably hard. He was one of the last Americans in a time when we were the best Marathon country in the world. We believed we trained as smart and as hard as anyone else and we raced accordingly. He devoted himself to teaching and coaching kids. His tough attitude will be missed.”

“Run steady Tom.”

~ WANDERING IN A RUNNING WORLD ~

By Toni Reavis. April 20, 2017.

Bobby Hodge told LetsRun in 2004,

Tom Fleming was always a hard charger, a larger than life presence whether on the road in competition or at the post-race party where stories flew as fast as the miles had just hours before. With his black Prince John beard and 6’1” frame drawn down by mega 150-mile training weeks, T. Fleming toed the staring line with his fitness visible beneath the barest of singlets, frame in relief, energy up, engagement pending.

TOM FLEMING (1951 – 2017)

There was something chivalric about TF, who left us yesterday at age 65, much, much too soon, his mighty heart beating its last as he collapsed while coaching his Montclair Kimberley Academy team at a track meet in Verona, N. J. The running pack will not find another in its midst like him again anytime soon.

A Bloomfield, New Jersey native, Tom was twice New York City Marathon champion (1973 & `75) when the race had yet to leave its Central Park cocoon to bloom across all five boroughs. Twice more he was runner up in Boston (1973 & 1974) the one race he wanted more than any other, maybe even more than an Olympic medal. He was a fixture there, six top tens in all.

As a young post-collegiate runner TF was one of the great knight-errants of the sport at a time when it was still being done mostly for adventure, traveling where whimsy and invitation led, repping his country, winner at home at the Jersey Shore Marathon three times, but also in Cleveland in 1978 where I called my first big race outside Boston – he told me about of the headwind coming off the lake in the second half. He also took top honors in Washington D.C., Toronto, and most infamously in Los Angeles 1981 in the sport’s first openly professional race, the $100,000 Jordache Los Angeles Pro-Am Marathon.

There, as he did in seemingly every race, Tom placed himself at the point of attack and pressed, going where the action was, mostly causing it himself, knowing his was a game of strength rather than pure speed. In Boston and at the five-borough New York City races his tactic ended up serving as de facto pacing for the bigger talents, but in L.A. 1981 he pulled free after the first mile to win by more than three minutes in 2:13:44. The win was worth $25,000, and he proudly carried the title of the sport’s first professional runner throughout his life, though he had claimed it before the category had ever officially existed. As recently as October 2015 Tom still wanted more for those who had followed in his footsteps.

“I’m still discouraged that today our sport hasn’t moved with much speed in acquiring more prize money at road races. There should be a $250,000 purse to win the New York City Marathon today. USATF still doesn’t let athletes have numerous sponsorships on their race singlets. The sport needs help coming from outside the business of running.”

A Jersey man through and through, Tom believed in engagement, and was fearless, whether in competition or in voicing his opinions about the politics of the sport. And so was he a running store owner, coach, race promoter, mentor, and always a full-throated running raconteur.

For the last 18 years he taught and coached at Montclair Kimberly Academy where his charisma and talents helped shape young lives. How fortunate they were to have someone like Tom as a leader. In 2013 he was inducted into the Road Runners Club of America Distance Running Hall of Fame and one year later was honored at the National Distance Running Hall of Fame in Utica, N.Y.