“The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into frustrated fury about everything – and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”

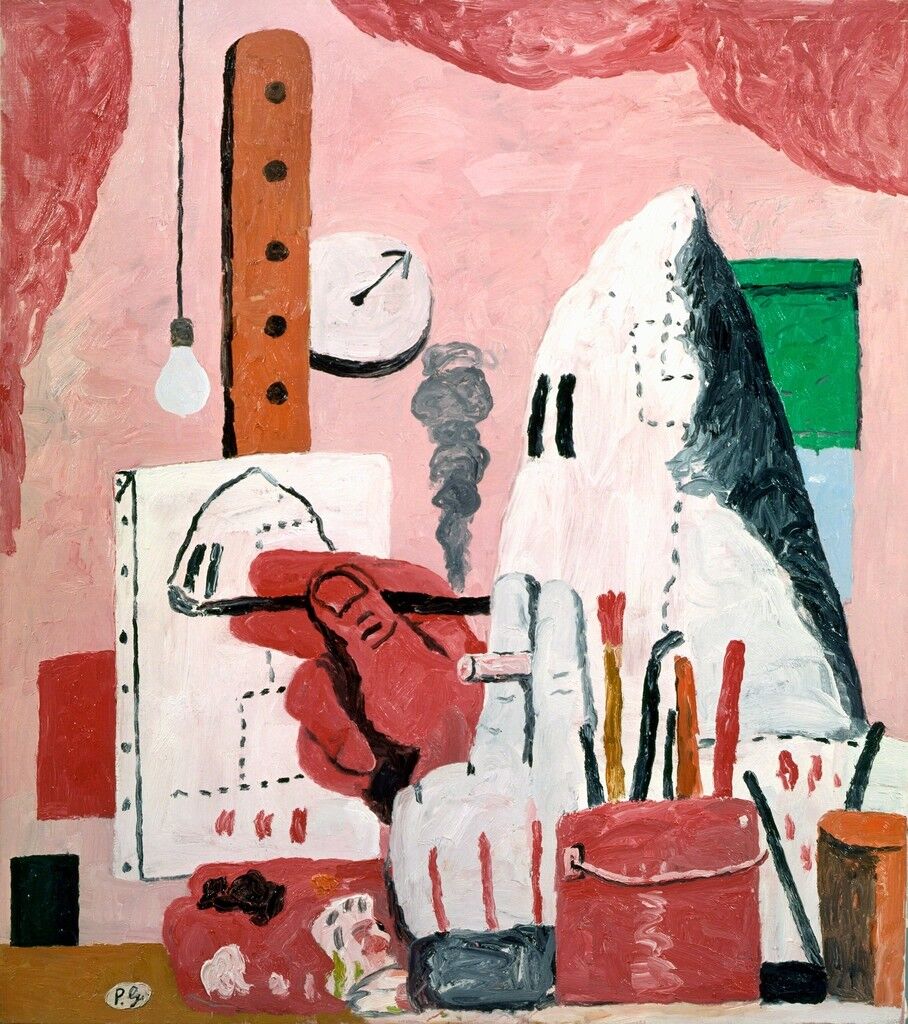

Best known for his cartoonish paintings and drawings from the late 1960s onwards, Philip Guston audaciously returned to figuration at the height of Abstract Expressionism. Guston created a lively cast of characters rendered in bold brushwork—sinister, hooded figures reminiscent of the Ku Klux Klan; cyclopean heads; and disembodied limbs. Seemingly mundane objects, such as bare light bulbs, shoes, cigarettes, and bricks were also imbued with personal meaning. A muralist with the government-funded Federal Art Project in the 1930s, an Abstract Expressionist in the 1950s and ‘60s, and a figurative painter in the last decades of his life, Guston is regarded as a leading figure in the creation of a new style of painting known as Neo-Expressionism.

– artsy.net.

Why AbEx Painter Philip Guston’s Return to Figuration Enraged the Art World

By Jackson Arn for Artsy.net. Oct 10, 2018

Bob Dylan went electric. Michael Jordan switched to baseball. Bill Murray got serious. And in 1967, after more than a decade at the forefront of Abstract Expressionism, the painter Philip Guston returned to representational art.

There’s no simple reason why artists and entertainers decide to move off the beaten path, but in every one of the cases listed above, the sudden career shifts were attacked by critics and fans alike. As punishment for abandoning the forms that brought them acclaim (folk, basketball, comedy, Abstract Expressionism), they were accused of opportunism, narcissism, or plain stupidity.

All of these insults—and plenty of others—were lobbed at Guston in the aftermath of his 1970 exhibition at Marlborough Gallery in Manhattan. After three productive years working in Upstate New York, the artist, then in his late fifties, unveiled 33 new paintings, many of which featured cartoonish, cone-headed figures that looked suspiciously like Klansmen covered in blood. Others depicted sinisterly banal piles of boots, clocks, hands, and light bulbs, all sketched in the same chunky red and black lines.

It would be difficult to imagine anything further from the sort of work that American art critics were then championing—and which Guston himself had been producing for years. The paintings didn’t jive with Clement Greenberg’s still-influential definition of modernism, which pooh-poohed any form of representation violating the “purity” and “ineluctable flatness” of the picture plane. But nor were they ironic and artificial, like the Pop art Leo Steinberg had praised in the Partisan Review. The New York art scene couldn’t decide exactly what was wrong with Guston’s recent work—only that it was a wretched failure.

In one of his earliest pieces as Time magazine’s art critic, Robert Hughes sneered at the perceived anachronism of Guston’s Klansmen—figures, he suggested, that could provide no real insight into the present moment. And in a masterpiece of snark composed for the New York Times, Hilton Kramer called Guston “a mandarin pretending to be a stumblebum,” the implication being that the artist was affecting a crude, “primitive” style simply because such a style had become trendy, thanks to painters such as Red Grooms and Wayne Thiebaud. Worst of all, Guston was “a colonizer rather than a pioneer”—an observation Kramer thought brilliant enough to make twice in his 1,000-word review.

In hindsight, Kramer’s remarks say relatively little about Guston and a lot about the New York critical establishment. Kramer and his peers were writing in an era when the logic of the stock market had begun to infect collectors and critics alike—an era when, as Hughes himself would later complain, novelty was the highest virtue and art that “looked ‘radical’ without being so” was praised to death. In such a climate, there could be no nastier insult than to accuse an artist of reaching the finish line second.

Guston deserved better. He began his career as a politically-minded muralist in the early 1930s. He became a prominent artist for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, painting ambitious, regional American scenes that oscillated between the personal and the propagandistic. After a decade of teaching in Iowa, Missouri, and New York, he began flirting with Abstract Expressionism, the movement made famous by his high school classmate Jackson Pollock.

But Guston was no copycat. Though they share a handful of aesthetic principles, his paintings from the 1950s don’t look much like Pollock’s—or Mark Rothko’s, or Willem de Kooning’s, for that matter. His mid-career masterpiece, Zone (1953–54), for instance, is calmer and less ostentatious than almost any of Pollock’s mature works, a low hum beside his former classmate’s loud splatters. It’s telling that Guston, when asked how he’d categorize his art, preferred the New York School to Abstract Expressionism: The latter is an “ism” with strict, changeless rules; the former a loose, open-ended term for a group of artists who happened to be in the same place at the same time.

The irony of Abstract Expressionism, as Tom Wolfe pointed out in his controversial 1975 polemic The Painted Word, is that what began as a revolt against the dogma of “academic art” eventually hardened into an equally severe dogma. A painter as restlessly curious as Guston could never be totally comfortable with such a movement. By the late ’60s, he’d returned to representational painting, which he would continue to experiment with for the rest of his career. The Klansmen who appeared throughout his Marlborough exhibition evoked the brutishness and not-so-latent racism of the Nixon era, packing a political punch that no AbEx canvas could match.

They also alluded to an exceptionally painful side of Guston’s past. His parents, both Jewish, had fled from Odessa to the United States, and he grew up hearing about local crimes against Jews perpetrated by the Ku Klux Klan. It’s even been suggested that anti-Semitism contributed to his father’s suicide in 1923, when Guston was still a teenager. The 1970 exhibition, then, marked Guston’s attempt to grapple with issues—both personal and aesthetic—that he’d been pondering for a very long time. One can hardly imagine how it must have wounded him to be accused of a cheap grab at topicality.

In 1978, Roberta Smith—one of the few New York critics who saw the Marlborough show for what it was—wrote in Art in America: “Nothing is final with Guston. He isn’t after an exalted, ultimate statement in his art.” That’s both a thoughtful interpretation of his career and a shrewd explanation of why his post-AbEx work was regarded as an act of betrayal. Unlike Rothko or Pollock, Guston rarely seemed to be trying to foster a sense of transcendence with his work; his representational paintings, like his earlier abstractions, instead had what Smith called “a solid, earthy grandeur.” Finding the best style through which to express this grandeur required a constant process of backtracking and reinventing, one that proved to be as crucial to his development as it was frustrating for his critics.

Guston continued to paint right up until his death in 1980. In the years following his Marlborough show, his reputation slowly climbed back toward where it had been in the ’50s; today, his work resides in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Tate Modern, and the Art Institute of Chicago, even though he’s still an order of magnitude below Pollock prestige-wise (among museumgoers, if not painters).

At least Guston had the satisfaction of living long enough to hear some of his meaner critics recant. Hughes, for one, would later call him “a figurative artist of extraordinary power.” He, like so many other notable art critics, had been stunningly wrong about Guston’s swerve back to representation, but he had the good grace to admit it. The love of art (to amend another cultural milestone from 1970) means often having to say you’re sorry.

Philip Guston’s Daughter and Other Critics Speak Out Against Four Museums’ Decision to Postpone a Major Retrospective on the Artist

The museums say they will postpone the show to a time when “the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.”

By Sarah Cascone for The New York Times. September 25, 2020

A long-planned traveling Philip Guston retrospective has been postponed for three years over concerns about how the work will be received amid heightened racial tensions and ongoing protests both in the US and abroad.

This is actually the second delay for the show, titled “Philip Guston Now,” which was announced in June 2019. It was originally set to open June 7, 2020, at National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, before traveling to the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Tate Modern in London, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Those dates were pushed back to July 2021 due to extended museum closures. Now, curators plan to completely rethink the show ahead of a newly set 2024 opening.

“The racial justice movement that started in the US and radiated to countries around the world, in addition to challenges of a global health crisis, have led us to pause,” the four museums said in a joint statement posted on the National Gallery website on Monday. “We feel it is necessary to reframe our programming and, in this case, step back, and bring in additional perspectives and voices to shape how we present Guston’s work to our public. That process will take time.”

Representatives for the museums did not respond to requests for comment. But the unspoken concern likely involves the paintings Guston began making in the late 1960s that feature hooded Ku Klux Klan figures. The exhibition was set to have featured 25 drawings and paintings from that body of work, according to ARTnews.

The postponement has been met with opposition from Musa Mayer, the artist’s daughter and head of the Guston Foundation. “Half a century ago, my father made a body of work that shocked the art world,” Mayer said in a statement. “Not only had he violated the canon of what a noted abstract artist should be painting at a time of particularly doctrinaire art criticism, but he dared to hold up a mirror to white America, exposing the banality of evil and the systemic racism we are still struggling to confront today.”

Regarding Guston’s Klan figures, Mayer said, “They plan, they plot, they ride around in cars smoking cigars. We never see their acts of hatred. We never know what is in their minds. But it is clear that they are us. Our denial, our concealment,” she added. “My father dared to unveil white culpability, our shared role in allowing the racist terror that he had witnessed since boyhood, when the Klan marched openly by the thousands in the streets of Los Angeles.”

The art historian and curator Darby English told the New York Times that the decision to postpone the show was “cowardly and patronizing, an insult to art and the public alike.” Guston’s paintings were “thoughtfully created in identification with history’s victims,” English said, adding that “[i]t should be part of one’s attitude to see them as opportunities to think, to improve thinking, to sharpen perception, to talk to one another,” and not “to grimly proceed with one’s head in the sand, avoiding difficult conversations because you think the timing is bad.”

Guston himself called the works self-portraits. “I perceive myself as being behind the hood,” he was quoted in the 2019 publication MoMA Highlights: 375 works From the Museum of Modern Art New York. “I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil?”

Robert Storr, who this month published a biography of the artist, Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting, [I should get that, I thought. $85! – JDW] told the Art Newspaper that the postponement was triggered by “pushback from staff about an anti-lynching image from the 1930s, which was in effect the predicate for all of Guston’s later Ku Klux Klan imagery.”

“If the National Gallery of Art, which has conspicuously failed to feature many artists-of-color, cannot explain to those who protect the work on view that the artist who made it was on the side of racial equality, no wonder they caved to misunderstanding in Trump times,” Storr added.

Museums have increasingly faced criticism in recent years for exhibiting work that addresses issues of racial violence.

The 2017 Whitney Biennial sparked controversy for including Dana Schutz’s Open Casket, a painting of Emmett Till, whose brutal 1955 lynching made headlines when his mother insisted on an open-casket funeral. Detractors accused Schutz, who is white, of capitalizing on Black suffering, and called for the painting’s destruction.

More recently, the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland canceled an exhibition of Afro-Latino artist Shaun Leonardo’s drawings of victims of police brutality due to community objections. The museum’s director, Jill Snyder, apologized and resigned. (The exhibition is now on view at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art and will travel to the Bronx Museum of the Arts in January.)

The upcoming exhibition was to have been Guston’s first US retrospective in 15 years, including some 125 paintings and 70 drawings.

Websites for the show at its first two venues, the National Gallery and the Tate, have been taken offline since the postponement announcement. Neither museum directly addressed the KKK imagery. The Tate mentioned Guston’s ’70s-era “paintings populated by cartoonish figures,” noting that they were not initially well-received by critics, but “established Guston as one of the most influential painters of the late 20th century.”

The museums will still publish the catalogue for the exhibition as originally planned, with essays from the four curators: Harry Cooper, Alison de Lima Greene, Mark Godfrey, and Kate Nesin.

Godfrey, senior curator of international art at the Tate Modern, has spoken out against the postponement on Instagram. “Cancelling or delaying the exhibition is probably motivated by the wish to be sensitive to the imagined reactions of particular viewers, and the fear of protest,” he wrote. “However, it is actually extremely patronizing to viewers, who are assumed not to be able to appreciate the nuance and politics of Guston’s works.”

The museums’ joint statement says that they “remain committed to Philip Guston and his work,” and that they hope to stage the show at a time when “we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.”

Mayer believes that moment is already here. “These paintings meet the moment we are in today,” she said. “The danger is not in looking at Philip Guston’s work, but in looking away.”

Artists slam decision to postpone exhibition of Philip Guston’s KKK paintings

By Oscar Holland for CNN. October 1, 2020.

Almost 100 art industry figures have called on four museums to reverse plans to postpone a major Philip Guston retrospective featuring some of the painter’s depictions of the Ku Klux Klan.

In an open letter published by New York-based journal Brooklyn Rail, the group of artists, curators, critics and scholars said they were “shocked and disappointed” by the decision to delay the show, which had been set to open in London next year before traveling to the US, until 2024.

The retrospective, titled “Philip Guston Now,” was due to bring together 125 paintings and 70 drawings by the American Canadian painter, who died in 1980. Among them were a number of artworks showing hooded Klansmen, which Guston — the son of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants — painted as part of his commentary on racial violence and American identity.

Last week, however, exhibition organizers announced that they were delaying the show by three years, citing the emergence of worldwide conversations about racial justice.

The four host museums — London’s Tate Modern, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and its namesake in Houston — said that they were using the extra time to seek “additional perspectives and voices” on how to present the artworks. In a joint statement, the museums’ directors explained that they were postponing the exhibition “until a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.

“Speaking to the art industry website Artnews, a representative for Washington’s National Gallery of Art added that organizers were worried that the “painful” images might have been “misinterpreted.”

But the decision was slammed by the letter’s signatories, which include contemporary artists Nicole Eisenman and Matthew Barney. The letter was also signed by a number of prominent African American artists, including Lorna Simpson, Charles Gaines and Stanley Whitney.

Describing the move as an “illustration of ‘white’ culpability,” the group accused the four institutions of shirking their responsibility to present the “depth and complexity” of Guston’s work.

“They fear controversy,” read the letter, which has attracted more than 900 additional signatures from the public. “They lack faith in the intelligence of their audience. And they realize that to remind museum-goers of White supremacy today is not only to speak to them about the past, or events somewhere else. It is also to raise uncomfortable questions about museums themselves — about their class and racial foundations.

“Hiding away images of the KKK will not serve that end,” it added. “Quite the opposite.”

‘Fascinated’ by evil

Part of the New York School art movement alongside figures like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, Guston came to prominence in the 1950s. Although best known at the time — like many of his contemporaries — for works of Abstract Expressionism, he began producing more figurative paintings in the late 1960s. Among these later works were a number of cartoonish images of KKK members, whom he often depicted driving or smoking.

As well as being a Jewish artist commenting on an organization with a long history of antisemitism, the paintings were also personal reflections on Guston’s own sense of culpability. The artist even described them as “self-portraits.”

“The idea of evil fascinated me,” he once explained, according to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, adding: “I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil?”Related video: How do you fall in love with art?The opening of “Philip Guston Now” had already been delayed by more than eight months due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Rescheduled to open in London in February 2021, it would have been the first major retrospective of the artist’s work in over 15 years.But while the paintings have been shown at museums in the years since, art institutions are now facing increased scrutiny to reflect on their own collections and curatorial decisions in light of the Black Lives Matter movement and ongoing protests for racial justice.

The four museums said they remained “committed” to Guston and his work, but argued that the social context had changed in the five years since they began work on the exhibition.

“The racial justice movement that started in the US and radiated to countries around the world, in addition to challenges of a global health crisis, have led us to pause,” the joint statement read. “As museum directors, we have a responsibility to meet the very real urgencies of the moment.”

The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and Tate Modern did not immediately respond to CNN’s request for comment.

Philip Guston’s KKK Paintings: Why an Abstract Painter Returned to Figuration to Confront Racism

BY Alex Greenberger for ArtNews.com. September 30, 2020 .

In 1930, Philip Guston went to work on Conspirators, a tall painting featuring a trio of Ku Klux Klan members clustered in the midst of mysterious architectural elements. Their heads were bowed, and their hands brandished clubs and other weapons. Three years later, the painting went on view in Los Angeles at the Stanley Rose bookshop. But in a cruel twist of fate, people who had donned pointed hoods similar to the ones featured in the work ended up destroying Conspirators and various other works by Guston—with members of the Los Angeles Police Department, working with the Klan and the veterans’ organization the American Legion, shredding the works before the artist’s eyes.

Around the time of that fateful show, the KKK had taken hold in Orange County, with high-ranking civic officials joining the group to push racist, nativist ideologies in violent ways. Guston, a Jew whose people were among those being targeted by the KKK, encountered the Klan’s activities there and grew horrified by what he saw. “He was not only a first-generation Jewish immigrant whose family had fled pogroms in Russia,” Musa Mayer, the artist’s daughter, told ARTnews, “but was in a larger sense committed to bearing witness and documenting injustice and inhumanity whenever it occurred.”

Guston worked in a number of artistic modes, from Renaissance-inspired figuration to formally accomplished abstraction. But no part of his oeuvre is as cryptic, strange, and difficult as his paintings and drawings of Klansmen. Their message is in certain ways clear, as Guston was affiliated very leftist groups early on in his career. (“This isn’t a guy who’s trying to promote the Klan,” Michael Auping, a curator who organized a Guston retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art Fort Worth in Texas, said recently.) But in their bracing acknowledgment of racism, they have had a tendency to provoke—as evidenced by the postponement last week of a Guston retrospective after the four museums presenting came to fear that audiences might not understand the full meaning of Guston’s KKK work.

Guston’s art of the 1930s shocked initially because it so baldly attacked its subject matter. Conspirators was created in the same style as a work made on commission for the Communist Party-affiliated John Reed Club, which asked Guston to respond to the state of the “American Negro.” The work he created focused on the Scottsboro Boys, nine Black teenagers who were falsely accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931. In one of Guston’s panels, a Klansman whips a nearly nude figure tied to a stake that looks like the Washington Monument. (That work was also destroyed in the Stanley Rose police raid.)

In a newly published monograph on Guston, curator Robert Storr writes, “In the ideologically polarized climate of that period—one that frighteningly anticipated the antagonism of the right-wing backlash in the United States culminating in the Trump era—the violence Guston allegorically portrayed in effect triggered an eruption of the real thing. This first trial by fire made it plain that although political art may not have the capacity to change the world, it can draw the evils that threaten society into the open, where they can be seen for what they are. It was a lesson the artist would not forget.”

Klansmen disappeared from Guston’s art for a while, after periods in which the artist variously took up tableaux inspired by Mexican muralism and abstractions similar to those of other artists active during the postwar era. But then they grandly returned nearly four decades later, in one of the artist’s most iconic bodies of work.

By then, Guston had been known as an acclaimed abstract painter. So it disappointed many when he returned to figuration with aplomb, painting mysterious images in which cartoonish-looking cups, heads, easels, and other visions were depicted against vacant beige backgrounds. “People whispered behind his back: He’s out of his mind, and this isn’t art,” Auping said. “He could have ruined his reputation, and some people said he did.”

As his colleagues looked on in horror, Guston began pushing his figuration even further, with Klansmen back again in his canvases. In the 1930s works, his hooded figures were rendered with a level of realism, their robes intricately rendered with chiaroscuro lighting. Starting in 1968, however, they were rendered with a kind of jokiness, their pointed hoods appearing poorly sewn and droopy. They often have big red mitts for hands, and they often converse while puffing on cigarettes and riding packed in cars like clowns. In a few cases, his Klansmen are shown creating artworks.

Made in response to various instances of social upheaval in the U.S.—including the showdown between protesters and the police at the Democratic National Convention and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., both in 1968—Guston’s works do not shy away from violence. One titled Bad Times (1970) features two Klansmen riding in a car, with one pointing a handgun at a figure who seems to have been shot dead, his oversized feet sticking out from behind an urban edifice. “They were exciting because they reflected so much of what was happening in the world at that time in America, the civil rights disturbances and the marches and the fires and the anger and the disruption of everything,” dealer David McKee said, according to a text reprinted on the Philip Guston Foundation’s website. “And we would talk about his own early interests in taking a position against social injustice.”

Guston’s Klan works of the late ’60s and early ’70s nag at the minds of many viewers because they are hard to parse. Where are these jalopy-riding Klansmen going—to kill someone, to attend a meeting, to do something altogether more commonplace like visit a store or a bar? Why do some of the Klansmen appear to be sad? Why are their hands so big? And what’s with the giant maroon fingers that are sometimes shown pointing at them? Also, how can a Klansmen whose hood has no mouth-opening smoke a cigarette, anyway?

Guston chose to leave these sorts of questions open, though he sometimes described the works as “self-portraits,” alluding to the fact that he was trying to understand the racist ideologies that guided these people—which, he believed, may also exist inside him in some way. Asked to characterize Guston’s thinking, Auping imagined the artist saying, “The only way I can understand outside evil is if there is evil inside of me.”

Others have suggested complex autobiographical meanings for the works. For decades early in his life, Guston’s last name was Goldstein—before he renounced it in an attempt to mask his Jewish identity. During the 1960s, however, he led a quest to reconnect with his Jewish heritage. Could the hooded figures some allude to the way he cloaked his own identity, keeping it out of view of the public? Art historian Donald Kuspit claimed as much when he wrote that the hood “signals his sense of being ‘faceless,’ that is, without an artistic identity. Is he also hiding, in shame, a so-called ‘Jewish face?’”

Whatever rich metaphorical content can be wrung from the paintings now, the works were thought to be duds when they debuted in 1970 at Marlborough Gallery in New York, which gave Guston the slot in its fall season with the greatest visibility. Critics lambasted the show—and alleged that the KKK works represented a poor attempt by Guston to stay relevant. In one famous review printed in Time magazine, Robert Hughes said it may have been “a little late in the century to mount an entire exhibition on the Ku Klux Klan.” In another printed in the New York Times, Hilton Kramer, a critic with aesthetically and politically conservative inclinations, gave Guston the harshest review of his career, calling the Klansmen paintings the “artistic equivalent of a ‘pseudoevent.’”

Since then, many artists have defended the Klan works. In the catalogue for the newly postponed Guston retrospective, Glenn Ligon writes, “Guston’s ‘hood’ paintings, with their ambiguous narratives and incendiary subject matter, are not asleep—they’re woke.” And in an essay for the same book, Trenton Doyle Hancock writes that “Guston describes something beyond the occasion, something lurking under the white hoods”—racism writ large.

Musa Mayer, the artist’s daughter, explained the paintings’ enduring power by quoting a New Yorker review of the Marlborough show by Harold Rosenberg: “Today, it would not be accurate to say that by picturing the banality of daily Klan life, ‘the personification of violence and tyranny puts politics at a distance.’”

The Strongest Reactions to the Philip Guston Show’s Postponement Miss Two Key Points.

Here’s What They Are—and Why They Matter.

https://news.artnet.com/opinion/philip-guston-now-cancellation-1914529