“It was as if I’d destroyed Hitler and his Aryan-supremacy, anti-Negro, anti-Jew viciousness.”

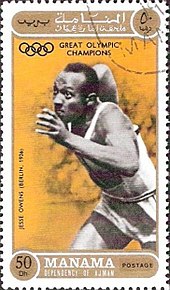

James Cleveland “Jesse” Owens (September 12, 1913 – March 31, 1980) was an American track and field athlete and four-time gold medalist in the 1936 Olympic Games.

Owens specialized in the sprints and the long jump and was recognized in his lifetime as “perhaps the greatest and most famous athlete in track and field history”. He set three world records and tied another, all in less than an hour, at the 1935 Big Ten track meet in Ann Arbor, Michigan—a feat that has never been equaled and has been called “the greatest 45 minutes ever in sport”.

He achieved international fame at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany, by winning four gold medals: 100 meters, long jump, 200 meters, and 4 × 100-meter relay. He was the most successful athlete at the Games and, as a black man, was credited with “single-handedly crushing Hitler’s myth of Aryan supremacy”, although he “wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the President, either”.[

The Jesse Owens Award is USA Track and Field’s highest accolade for the year’s best track and field athlete. Owens was ranked by ESPN as the sixth greatest North American athlete of the 20th century and the highest-ranked in his sport. In 1999, he was on the six-man short-list for the BBC’s Sports Personality of the Century.

Early life and education

Jesse Owens, originally known as J.C., was the youngest of ten children (three girls and seven boys) born to Henry Cleveland Owens (a sharecropper) and Mary Emma Fitzgerald in Oakville, Alabama, on September 12, 1913. He was the grandson of a slave. At the age of nine, he and his family moved to Cleveland, Ohio, for better opportunities, as part of the Great Migration, when 1.5 million African Americans left the segregated South for the urban and industrial North. When his new teacher asked his name (to enter in her roll book), he said “J.C.”, but because of his strong Southern accent, she thought he said “Jesse”. The name stuck, and he was known as Jesse Owens for the rest of his life.

As a youth, Owens took different menial jobs in his spare time: he delivered groceries, loaded freight cars and worked in a shoe repair shop while his father and older brother worked at a steel mill. During this period, Owens realized that he had a passion for running. Throughout his life, Owens attributed the success of his athletic career to the encouragement of Charles Riley, his junior high school track coach at Fairmount Junior High School. Since Owens worked in a shoe repair shop after school, Riley allowed him to practice before school instead.

Owens and Minnie Ruth Solomon (1915–2001) met at Fairmont Junior High School in Cleveland when he was 15 and she was 13. They dated steadily through high school. Ruth gave birth to their first daughter, Gloria, in 1932. They married on July 5, 1935, and had two more daughters together: Marlene, born in 1937, and Beverly, born in 1940. They remained married until his death in 1980.

Owens first came to national attention when he was a student of East Technical High School in Cleveland; he equaled the world record of 9.4 seconds in the 100 yards (91 m) dash and long-jumped 24 feet 9+1⁄2 inches (7.56 m) at the 1933 National High School Championship in Chicago.

Career

Ohio State University

Owens attended the Ohio State University after his father found employment, which ensured that the family could be supported. Affectionately known as the “Buckeye Bullet” and under the coaching of Larry Snyder, Owens won a record eight individual NCAA championships, four each in 1935 and 1936. (The record of four gold medals at the NCAA was equaled only by Xavier Carter in 2006, although his many titles also included relay medals).

Though Owens enjoyed athletic success, he had to live off campus with other African-American athletes. When he traveled with the team, Owens was restricted to ordering carry-out or eating at “blacks-only” restaurants. Similarly, he had to stay at “blacks-only” hotels. Owens did not receive a scholarship for his efforts, so he continued to work part-time jobs to pay for school.

Day of days

25 May 1935 is remembered as the day when Jesse Owens established 4 world records in athletics. Owens achieved track and field immortality in a span of 45 minutes on May 25, 1935, during the Big Ten meet at Ferry Field in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he set three world records and tied a fourth. He equaled the world record for the 100-yard dash (9.4 seconds) (not to be confused with the 100-meter dash), and set world records in the long jump (26 feet 8+1⁄4 inches or 8.13 metres, a world record that would last for 25 years); 220-yards (201.2 m) sprint (20.3 seconds); and 220-yard low hurdles (22.6 seconds, becoming the first to break 23 seconds). Both 220-yard records may also have beaten the metric records for 200 meters (flat and hurdles), which would count as two additional world records from the same performances. In 2005, University of Central Florida professor of sports history Richard C. Crepeau chose these wins on one day as the most impressive athletic achievement since 1850.

1936 Berlin Summer Olympics

On December 4, 1935, NAACP Secretary Walter Francis White wrote a letter to Owens but never sent it. He was trying to dissuade Owens from taking part in the 1936 Summer Olympics in Nazi Germany, arguing that an African American should not promote a racist regime after what his race had suffered at the hands of white racists in his own country. In the months prior to the Games, a movement gained momentum in favor of a boycott.

Owens was convinced by the NAACP to declare: “If there are minorities in Germany who are being discriminated against, the United States should withdraw from the 1936 Olympics”. Yet he and others eventually took part after Avery Brundage, president of the American Olympic Committee branded them “un-American agitators”.

In 1936, Owens and his United States teammates sailed on the SS Manhattan and arrived in Germany to compete at the Summer Olympics in Berlin. According to fellow American sprinter James LuValle, who won the bronze in the 400 meters, Owens arrived at the new Olympic stadium to a throng of fans, many of them young girls yelling “Wo ist Jesse? Wo ist Jesse?” (“Where is Jesse? Where is Jesse?”).

Just before the competitions, founder of Adidas athletic shoe company Adi Dassler visited Owens in the Olympic village and persuaded Owens to wear Gebrüder Dassler Schuhfabrik shoes; this was the first sponsorship for a male African American athlete.

On August 3, Owens won the 100m dash with a time of 10.3 seconds, defeating a teammate and a college friend Ralph Metcalfe by a tenth of a second and defeating Tinus Osendarp of the Netherlands by two tenths of a second. On August 4, he won the long jump with a leap of 8.06 metres (26 ft 5 in) (3¼ inches short of his own world record). He later credited this achievement to the technical advice that he received from Luz Long, the German competitor whom he defeated. On August 5, he won the 200m sprint with a time of 20.7 seconds, defeating teammate Mack Robinson (the older brother of Jackie Robinson).

On August 9, Owens won his fourth gold medal in the 4 × 100m sprint relay when head coach Lawson Robertson replaced Jewish-American sprinters Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller with Owens and Ralph Metcalfe, who teamed with Frank Wykoff and Foy Draper to set a world record of 39.8 seconds in the event. Owens had initially protested the last-minute switch, but assistant coach Dean Cromwell said to him, “You’ll do as you are told.”

Owens’s record-breaking performance of four gold medals was not equaled until Carl Lewis won gold medals in the same events at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. Owens had set the world record in the long jump with a leap of 8.13 m (26 ft 8 in) in 1935, the year before the Berlin Olympics, and this record stood for 25 years until it was broken in 1960 by countryman Ralph Boston. Coincidentally, Owens was a spectator at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome when Boston took the gold medal in the long jump.

The long-jump victory is documented, along with many other 1936 events, in the 1938 film Olympia by Leni Riefenstahl. On August 1, 1936, Nazi Germany’s leader Adolf Hitler shook hands with the German victors only and then left the stadium. International Olympic Committee president Henri de Baillet-Latour insisted that Hitler greet every medalist or none at all. Hitler opted for the latter and skipped all further medal presentations.

Owens first competed on Day 2 (August 2), running in the first (10:30 a.m.) and second (3:00 p.m.) qualifying rounds for the 100 meters final; he equaled the Olympic and world record in the first race and broke them in the second race, but the new time was not recognized, because it was wind-assisted. Later the same day, Owens’s African-American team-mate Cornelius Johnson won gold in the high jump final (which began at 5:00 p.m.) with a new Olympic record of 2.03 meters.

Hitler did not publicly congratulate any of the medal winners this time; even so, the communist New York City newspaper the Daily Worker claimed Hitler received all the track winners except Johnson and left the stadium as a “deliberate snub” after watching Johnson’s winning jump. Hitler was subsequently accused of failing to acknowledge Owens (who won gold medals on August 3, 4 (two), and 9) or shake his hand. Owens responded to these claims at the time:

Hitler had a certain time to come to the stadium and a certain time to leave. It happened he had to leave before the victory ceremony after the 100 meters [race began at 5:45 p.m.]. But before he left I was on my way to a broadcast and passed near his box. He waved at me and I waved back. I think it was bad taste to criticize the “man of the hour” in another country.

In an article dated August 4, 1936, the African-American newspaper editor Robert L. Vann describes witnessing Hitler “salute” Owens for having won gold in the 100m sprint (August 3):

And then;… wonder of wonders;… I saw Herr Adolph [sic] Hitler, salute this lad. I looked on with a heart which beat proudly as the lad who was crowned king of the 100 meters event, get an ovation the like of which I have never heard before. I saw Jesse Owens greeted by the Grand Chancellor of this country as a brilliant sun peeped out through the clouds. I saw a vast crowd of some 85,000 or 90,000 people stand up and cheer him to the echo.

In 2014, Eric Brown, British fighter pilot and test pilot, the Fleet Air Arm’s most decorated living pilot, stated in a BBC documentary: “I actually witnessed Hitler shaking hands with Jesse Owens and congratulating him on what he had achieved”.

Additionally, an article in The Baltimore Sun in August 1936 reported that Hitler sent Owens a commemorative inscribed cabinet photograph of himself. Later, on October 15, 1936, Owens repeated this allegation when he addressed an audience of African Americans at a Republican rally in Kansas City, remarking: “Hitler didn’t snub me—it was our president who snubbed me. The president didn’t even send me a telegram.”

Owens’s success at the games caused consternation for Hitler, who was using them to show the world a resurgent Nazi Germany. He and other government officials had hoped that German athletes would dominate the games. Nazi minister Albert Speer wrote that Hitler “was highly annoyed by the series of triumphs by the marvelous colored American runner, Jesse Owens. People whose antecedents came from the jungle were primitive, Hitler said with a shrug; their physiques were stronger than those of civilized whites and hence should be excluded from future games.”

In Germany, Owens had been allowed to travel with and stay in the same hotels as whites, at a time when African Americans in many parts of the United States had to stay in segregated hotels that accommodated only blacks. When Owens returned to the United States, he was greeted in New York City by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia.

During a Manhattan ticker-tape parade in his honor along Broadway’s Canyon of Heroes, someone handed Owens a paper bag. Owens paid it little mind until the parade concluded. When he opened it up, he found that the bag contained $10,000 in cash. Owens’s wife Ruth later said: “And he [Owens] didn’t know who was good enough to do a thing like that. And with all the excitement around, he didn’t pick it up right away. He didn’t pick it up until he got ready to get out of the car”.

After the parade, Owens was not permitted to enter through the main doors of the Waldorf Astoria New York and instead forced to travel up to the reception honoring him in a freight elevator. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) never invited Jesse Owens to the White House following his triumphs at the Olympic Games. When the Democrats bid for his support, Owens rejected those overtures: as a staunch Republican, he endorsed Alf Landon, Roosevelt’s Republican opponent in the 1936 presidential race.

Owens joined the Republican Party after returning from Europe and was paid to campaign for African American votes for the Republican presidential nominee Alf Landon in the 1936 presidential election.

Speaking at a Republican rally held in Baltimore on October 9, 1936, Owens said: “Some people say Hitler snubbed me. But I tell you, Hitler did not snub me. I am not knocking the President. Remember, I am not a politician, but remember that the President did not send me a message of congratulations because, people said, he was too busy.”

Life after the Olympics

Owens was quoted saying the secret behind his success was, “I let my feet spend as little time on the ground as possible. From the air, fast down, and from the ground, fast up.”

After the games had ended, the entire Olympic team was invited to compete in Sweden. Owens decided to capitalize on his success by returning to the United States to take up some of the more lucrative endorsement offers. United States athletic officials were furious and withdrew his amateur status, which immediately ended his career. Owens was angry and stated that “A fellow desires something for himself.” Owens argued that the racial discrimination he had faced throughout his athletic career, such as not being eligible for scholarships in college and therefore being unable to take classes between training and working to pay his way, meant he had to give up on amateur athletics in pursuit of financial gain elsewhere.

Owens returned home from the 1936 Olympics with four gold medals and international fame, yet had difficulty finding work. He took on menial jobs as a gas station attendant, playground janitor, and manager of a dry cleaning firm. He also raced against amateurs and horses for cash.

https://www.theguardian.com/observer/osm/story/0,,362001,00.html

Owens was prohibited from making appearances at amateur sporting events to bolster his profile, and he found out that the commercial offers had all but disappeared. In 1937, he briefly toured with a twelve-piece jazz band under contract with Consolidated Artists but found it unfulfilling. He also made appearances at baseball games and other events. Finally, Willis Ward—a friend and former competitor from the University of Michigan—brought Owens to Detroit in 1942 to work at Ford Motor Company as Assistant Personnel Director. Owens later became a director, in which capacity he worked until 1946.

In 1946, Owens joined Abe Saperstein in the formation of the West Coast Negro Baseball League, a new Negro baseball league; Owens was Vice-President and the owner of the Portland (Oregon) Rosebuds franchise. He toured with the Rosebuds, sometimes entertaining the audience in between doubleheader games by competing in races against horses. The WCBA disbanded after only two months.

Owens helped promote the exploitation film Mom and Dad in African American neighborhoods. He tried to make a living as a sports promoter, essentially an entertainer. He would give local sprinters a ten- or twenty-yard start and beat them in the 100-yd (91-m) dash. He also challenged and defeated racehorses; as he revealed later, the trick was to race a high-strung Thoroughbred that would be frightened by the starter’s shotgun and give him a bad jump. Owens said, “People say that it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse, but what was I supposed to do? I had four gold medals, but you can’t eat four gold medals.” On the lack of opportunities, Owens added, “There was no television, no big advertising, no endorsements then. Not for a black man, anyway.”

He traveled to Rome for the 1960 Summer Olympics, where he met the 1960 100 meters champion Armin Hary of Germany, who had defeated American Dave Sime in a photo finish.

In 1965, Owens was hired as a running instructor for spring training for the New York Mets.

Owens ran a dry cleaning business and worked as a gas station attendant to earn a living, but he eventually filed for bankruptcy. In 1966, he was successfully prosecuted for tax evasion. At rock bottom, he was aided in beginning his rehabilitation. The government appointed him as a US goodwill ambassador. Owens traveled the world and spoke to companies such as the Ford Motor Company and stakeholders such as the United States Olympic Committee. After he retired, he owned racehorses.

Owens initially refused to support the black power salute by African-American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Summer Olympics. He told them:

The black fist is a meaningless symbol. When you open it, you have nothing but fingers – weak, empty fingers. The only time the black fist has significance is when there’s money inside. There’s where the power lies.

Four years later in his 1972 book I Have Changed, he revised his opinion:

I realized now that militancy in the best sense of the word was the only answer where the black man was concerned, that any black man who wasn’t a militant in 1970 was either blind or a coward.

Owens traveled to Munich for the 1972 Summer Olympics as a special guest of the West German government, meeting West German Chancellor Willy Brandt and former boxer Max Schmeling.

A few months before his death, Owens had unsuccessfully tried to convince President Jimmy Carter to withdraw his demand that the United States boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics in protest of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. He argued that the Olympic ideal was supposed to be observed as a time-out from war and that it was above politics.

Death

Owens was a pack-a-day cigarette smoker for 35 years, starting at age 32. Beginning in December 1979, he was hospitalized on and off with an extremely aggressive and drug-resistant type of lung cancer. He died of the disease at age 66 in Tucson, Arizona, on March 31, 1980, with his wife and other family members at his bedside. He was buried at Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago. The grave is inscribed “Jesse Owens 1936 Olympic Champion” and is set against the backdrop of the lake in the cemetery.

Although Jimmy Carter had ignored Owens’s request to cancel the Olympic boycott, the president issued a tribute to Owens after he died: “Perhaps no athlete better symbolized the human struggle against tyranny, poverty and racial bigotry.”

Legacy

The dormitory that Owens occupied during the Berlin Olympics has been fully restored into a living museum, with pictures of his accomplishments at the games, and a letter (intercepted by the Gestapo) from a fan urging him not to shake hands with Hitler. In 2016, the 1936 Olympic journey of the eighteen Black American athletes, including Owens, was documented in the film Olympic Pride, American Prejudice.

Awards and honors

- 1936: AP Athlete of the Year (Male)

- 1936: four English oak saplings, one for each Olympic gold medal, from the German Olympic Committee, planted. One of the trees was planted at the University of Southern California, one at Rhodes High School in Cleveland, where he trained, and one is rumored to be on the Ohio State University campus but has yet to be identified. The fourth tree was at the home of Jesse Owens’s mother but was removed when the house was demolished.

- 1970: inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame.

- 1976: awarded Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford.

- 1976: inducted into Silver Olympic Order for his quadruple victory in the 1936 games and his defense of sport and the ethics of sport.

- 1979: awarded Living Legend Award by President Jimmy Carter.

- 1980: asteroid newly discovered by Antonín Mrkos at the Kleť Observatory named 6758 Jesseowens.

- 1981: USA Track and Field created the Jesse Owens Award which is given annually to the country’s top track and field athlete.

- 1983: part of inaugural class into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame.

- 1984: street south of the Olympic Stadium in Berlin renamed Jesse-Owens-Allee

- 1984: secondary school Jesse Owens Realschule/Oberschule in Lichtenberg, Berlin named for Owens.

- March 28, 1990: posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President George H. W. Bush.

- 1990 and 1998: two U.S. postage stamps have been issued to honor Owens, one in each year.

- 1996: Owens’s hometown of Oakville, Alabama, dedicated the Jesse Owens Memorial Park and Museum in his honor at the same time that the Olympic Torch came through the community, 60 years after his Olympic wins. The Wall Street Journal of June 7, 1996, covered the event and noted this inscription on a bronze plaque at the park:

May this light shine forever

– Charles Ghigna

as a symbol to all who run

for the freedom of sport,

for the spirit of humanity,

for the memory of Jesse Owens.

- 1999: ranked the sixth greatest North American athlete of the twentieth century and the highest-ranked in his sport by ESPN.

- 1999: on the six-man shortlist for the BBC’s Sports Personality of the Century.

- 2001: Ohio State University dedicated Jesse Owens Memorial Stadium for track and field events. A sculpture honoring Owens occupies a place of honor in the esplanade leading to the rotunda entrance to Ohio Stadium. Owens competed for the Buckeyes on the track surrounding the football field that existed prior to the 2001 expansion of Ohio Stadium. The campus also houses three recreational centers for students and staff named in his honor.

- 2002: scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Owens on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

- 2009: at the 2009 World Athletic Championships in Berlin, all members of the United States Track and Field team wore badges with “JO” on them to commemorate Owens’s victories in the same stadium 73 years before.

- 2010: Ohio Historical Society proposed Owens as a finalist from a statewide vote for inclusion in Statuary Hall at the United States Capitol.

- November 15, 2010: the city of Cleveland renamed East Roadway, between Rockwell and Superior avenues in Public Square, Jesse Owens Way.

- 2012: 80,000 individual pixels in the audience seating area were used as a giant video screen to show footage of Owens running around the stadium in the London 2012 Summer Olympics opening ceremony, just after the Olympic cauldron had been lit.

- In Cleveland, Ohio, a statue of Owens in his Ohio State track suit was installed at Fort Huntington Park, west of the old Courthouse.

- Phoenix, Arizona named the Jesse Owens Medical Centre in his honor, as well as Jesse Owens Parkway.

- Jesse Owens Park, in Tucson, Arizona, is a center of local youth athletics there.

- For his contribution to sports in Los Angeles, Owens was honored with a Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum “Court of Honor” plaque by the Coliseum commissioners.

- in July 2018, Ohio Governor John Kasich dedicated the 75th state park Jesse Owens State Park. It is located on AEP reclaimed mining land south of Zanesville, OH.

Source: Wikipedia

Jesse Owens was the talk of the 1936 Olympics, but other African American athletes also performed Olympian feats. Of the 312 Americans, 18 were Black, according to NPR, and between them they won 14 medals (including eight gold) of the country’s total medal count of 56.

John Woodruff came from behind to win gold in the 800m. Archie Williams won the 400m (and later trained Tuskegee Airmen.) Cornelius Johnson broke the Olympic record to win gold in the high jump, while teammate David Albritton took silver. Hurdler Tidye Pickett became the first African American woman to compete in the Olympics, but broke her foot in the semi-finals. Owens beat two of his Black teammates to win two of his medals. Mack Robinson took silver in the 200m: you may recognize him as Jackie Robinson’s brother. And Ralph Metcalfe — who had beaten Owens in the 1932 Olympic qualifiers — took silver in the 100m. He also joined Owens in the record-breaking 100m relay, and later served in the House of Representatives.

There was racism within the US team. Louise Stokes was dropped from the 100m relay for a white runner. And Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller — the only Jewish members of the track team — were replaced with Owens and Metcalfe at the last minute, despite running faster than another team member. ESPN reported a rumor that the Nazis pressured US officials to make the switch.

Source: Grunge.com

American sprinters Louise Stokes and Tidye Pickett were pioneers both for feminism and for women in color in the 1930s. After missing out on the final American Olympic squad in 1932 thanks to a racial selection process (they were also kept separate from white runners and served food in their rooms), they were given their chance for the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Those, of course, were the extraordinary Olympics hosted in Berlin by Adolf Hitler, in which Jesse Owens produced a historical athletic performance to defy the Aryan rhetoric of the Nazi state.

At the Olympics themselves, Stokes was replaced by a white runner once again, but Tidye was given the chance to compete, getting to the semi-finals in the 80m hurdles before falling at a hurdle and being eliminated. They were the first two African-American women to be selected for an American squad, and Pickett herself was the first to ever compete.

https://allthatsinteresting.com/adolf-dassler